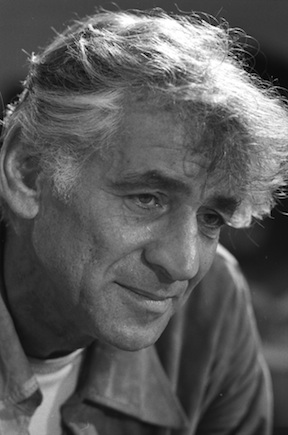

“The key to the mystery of a great artist is that for reasons unknown, he will give away his energies and his life to make sure that one note follows another…and leaves us with the feeling that something is right in the world.”

– Leonard Bernstein

By Victoria Mariconti

Of all the American classical musicians of the twentieth century, none was more influential than the pianist, conductor, and composer Leonard Bernstein (ΦBK, Harvard University, 1939). His unique tastes in music programming, his novel symphonic and popular compositions, and his passion for music education nurtured and transformed an initially nascent classical music community in the United States.

Leonard Bernstein (August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was the eldest son of Russian-Jewish immigrants Samuel Bernstein and Jennie Resnick. In spite of a blank musical pedigree, ten-year-old Bernstein quickly took to the piano that an aunt had stored in his family home. Leonard progressed quickly in his studies; he appeared on Boston radio shows and played in jazz clubs to support his piano lessons as a teenager. Leonard’s father was skeptical of his son’s career choice as it became increasingly apparent that he intended to pursue music. Nonetheless, Bernstein was allowed to major in music at Harvard University. As an undergraduate, Bernstein made several acquaintances that would serve him well in his professional career: the eminent composer-conductors Dimitri Mitropoulos and Aaron Copland emerged as key mentors to Bernstein during this formative time.

After a fruitful period of post-graduate study at the Curtis Institute and additional, successful networking with the classical music elite of Massachusetts and New York, Bernstein quickly rose to fame as a conductor and music director. In August 1943, Arthur Rodziński offered him the position of assistant conductor with the New York Philharmonic. His compositional career accelerated shortly thereafter: Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1, “Jeremiah,” won the New York Music Critics Circle Prize in 1944 for the best symphonic première of the season.

Bernstein’s prolific life as a conductor, composer, music director, educator, and cultural icon defies abbreviation; the capacity in which he dramatically exceeded his contemporaries, however, was the way in which he applied his gifts and fame to cultivate American musical life and serve as an ambassador between the United States and the international music community. Prior to Bernstein, the conductors of most major American symphonies were European émigrés such as his mentors Mitropoulos and Serge Koussevitzky of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Bernstein absorbed their conducting and music programming skills but cultivated his own persona to match his technical abilities on the podium.

In the post-World War II era, Bernstein appeared primarily as a guest conductor with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, and the Orchestre National de France. In 1953, Bernstein became the first American to conduct in Milan’s treasured opera house, “La Scala.”

Away from orchestras and scores, Bernstein passionately labored to educate young (and older) musicians. In particular, the televised series of his “Young People’s Concerts,” (1958-1972) inspired the subsequent generation of instrumentalists, composers, and conductors in America.

Perhaps Bernstein’s greatest talent lay in his ability to use music to respond to the world around him, and by doing so, help others make sense of the world. During the difficult weekend following President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, Bernstein altered the programming for the New York Philharmonic; each concert that weekend opened with the funeral march from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, Eroica, followed by silence rather than applause. On November 24, Bernstein conducted Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” in remembrance of the slain Kennedy. These gestures, in his own words, were the best acts of testimony and courage a musician could perform:

“This will be our reply to violence: To make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

Victoria Mariconti is a senior at Boston College majoring in music. She became a member of Phi Beta Kappa in her junior year. Boston College is home to the Omicron of Massachusetts Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.