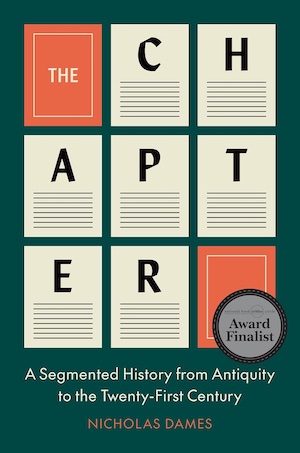

By Suzanne Keen

Shortlisted for ΦBK’s 2024 Christian Gauss Award

Like sidewalks, you notice them most when they aren’t where you want them. Dividing a 300-page novel into reasonable chunks for my students to read, I measure around a quarter-inch thickness with my thumb and open the book optimistically, hoping to have hit a break between chapters. “Read 1-101 for Monday” seems reasonable when the page range delivers you to a breathing space between the end of chapter four and the beginning of five, whereas “Read 200-300 for Wednesday” seems absurd if it picks up or ends in a page full of prose with no white space or comforting pause. Numbered or decorated with titles or epigraphs, surrounded by a little bit of white space at the beginning or end, or dignified with a full page break, chapters themselves, like the practice of chunking discourse into segments, remain more or less invisible to us—caught up in the flow of discourse and immersed in a book’s content—until we need a place to put our bookmark. Are we awake enough to read on until the next break?

Where did chapters come from? And how did chapters become such a natural part of lengthier works that books seem oppressive or forbidding when they lack them? In The Chapter, Nicholas Dames meditates at length and in lyrical detail about these flexible containers, units in sequence, that alternately tell us it’s OK to rest or demand our attention with vivid signposting. Sometimes a tool for dividing an existent text, as in the books of the Bible, sometimes an interruption, sometimes a marker for indexing content, sometimes a vehicle for promissory teasers, chapters lack a theory of their own and possess a deep history, often forgotten, of a development from an editorial apparatus to an aesthetic device in the novelist’s toolkit. Dames suggests that the chapter as a division of time within a story exists in tension with the division of a reader’s time, as “a unit of communication between narrator and reader that acknowledges, and sculpts, the time it takes to read.”

As Dames astutely observes, chapters speak to us about time though they can be conceptualized as containers or their divisions employed as a map. Ubiquitous and nearly invisible, chapters have entered our idioms about time, change, transitions, boundaries, and even our own mortality. Dames writes, “a chapter is very like many things, as long as those things have the qualities of stuttered motion, time experienced as space and space understood as an effect of time.” Having drunk deep at the Augustinian well, in which the present has no duration, Dames offers “a highly abbreviated intellectual history” to suggest how “prose, temporal divisibility, human will, and textual segmentation become tangled together in any consideration of how presentness could be felt or evoked.” Thus the medieval capitulators who aerated Arthurian legends with white space both modernized and made immediate the old tales; Caxton’s chapters were part of the value-added to his printed edition of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur (1485).

Dames brings a poetic sensibility and the zeal of a discoverer to his exposition. Organized mainly in chronological order, Dames’s discussion roves from the classics to the Gospels, to the earliest printed books, to the novel in early, Victorian, modern, and postmodern forms, to film and other media. Always informative and generously documented in rewarding endnotes, Dames’s account is both scholarly and playful, employing both traditional narratives of editorial controversy and empirical techniques of distant reading, some light narratology and also some good old-fashioned literary criticism.

Offered as a part of his interpretation of Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869), Dames’s taxonomy of chaptering techniques may be the single most teachable page in the whole book. Parsing them in terms of temporal orientation, affect, place of emphasis, and force, Dames offers options for 19th-century chapter rationales: 1) the incitation or signal; 2) the threshold crossing; 3) the suspended revelation; 4) tense relations (the “clock”); and 5) aspect relations (“point of view”). This rich little table could be the source of productive lesson plans designed to estrange student readers just enough from plot, character, and theme to see that a novel is made out of words deployed deliberately by a writer and to begin to grapple with the consequences of technical choices that are laid bare in and around chapter divisions.

Do you know how you can throw yourself off balance by noticing the frames of your own spectacles? It took me a while after reading The Chapter to stop seeing chapters, rather than seeing through them, or noticing them only intermittently as markers of my pace and progress. Enriched by reading Dames’s clever and learned account of The Chapter, I was nonetheless eager to capitulate to his subject’s insistence on its own invisibility and innocuousness, or intermittent handiness as a place to pause, or choose to carry on.

Suzanne Keen (ΦBK, Brown University) is Professor of English at Scripps College. She works on the novel and narrative empathy, most recently in Empathy and Reading: Affect, Impact, and the Co-Creating Reader (Routledge 2022).