By Svetlana Alpers

I have long loved Diego Velazquez’s portrait of Juan de Pareja in the Metropolitan Museum. At the top of the main staircase, I head straight, turn right, and wind through rooms to find it. It stops one dead: a classic Italian Renaissance portrait format — think Raphael’s Baldassare Castiglione — the person portrayed ½ length, head turned in ¾ view to the painter/viewer, bent right arm underlining and securing the triangulated format, and in this case there is the presence of a tawny face beneath a halo of dark hair, poised over a white collar roughed-in avoiding pictorial display, with a subtle line of buttons leading towards the single hand held above the canvas edge. The picture combines pictorial achievement with unique respect. Velázquez discovers the human significance of the man he depicts. Newly finished, it was acclaimed as a pictorial triumph when displayed with other pictures in 1650 at the Pantheon. Velázquez and Pareja were in Rome together, travelling on an art-gathering Italian trip at the behest of Phillip IV of Spain. (One wonders where the portrait went after that.)

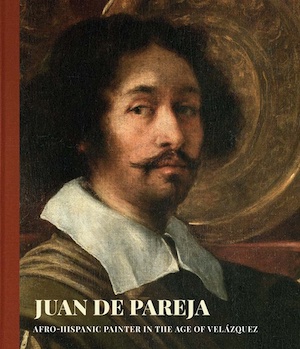

This publication about Juan de Pareja accompanies an exhibition at the Met on view until July 18. We have known the portrait is of Juan de Pareja, previously described as mulatto, here corrected to Afro-Hispanic, and previously described as Velazquez’s assistant, here corrected to enslaved studio assistant.

The fact that Juan de Pareja was enslaved to Velazquez is not new. Though the catalogue gives us a broader sense of what that meant in a Seville inhabited by African-Hispanics both freed and enslaved, and also what that meant among painters. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, for example, is noted to have had an enslaved assistant. But he did not choose to make a portrait of him. Nor is the fact new, nowhere I think mentioned in the materials that accompany this show, that in 1627 Velázquez won a competition for a painting of The Expulsion of the Moriscos (later destroyed in a palace fire) or that as court artist he spent years trying and finally succeeded in becoming a member of the distinguished Order of Santiago, which was devoted to expelling Jews and Muslims from Spain.

What then is the relationship between an artist’s life and an artist’s art?

Reviewers have been rightly enthusiastic about the show and catalogue. One remarked, “We’ll never look at the Portrait of Juan de Pareja the same way again.” Ok, but what exactly does the reviewer mean? She simply stops there. Most reviewers have picked away at Velázquez through the portrayal itself — claiming that Pareja was “compelled” to pose. But isn’t the pose of any sitter a negotiation with a painter? Because of the facts of this particular case, the reviewers’ comments seem to be in danger of confusing pictorial authority with enslavement.

The entry in the catalogue for the three Velázquez paintings of the [Black] Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus points out that the representation of a person of African descent in these three paintings is unprecedented in European Art. That is new to me about these paintings, and it is important for what we are looking at here. Doesn’t the impulse to paint a kitchen maid who is Black speak of the same man, Velázquez, who painted the portrait of Juan de Pareja?

For the first time in America a significant group of paintings by Juan de Pareja are hung together with his portrait by Velázquez, including an impressive Calling of St. Matthew, in which Pareja painted himself. It is interesting that he does not choose to work in the broadly Titianesque-Venetian manner of Velázquez. The catalog cleverly has Pareja by Pareja on the front cover and Pareja by Velázquez on the back. The difference between the two is worth considering.

While the recognition of Juan de Pareja as an artist is new to us today in New York, it is not new to the world. In the Introduction to the catalogue, passing mention is made of the fact that Pareja’s first biography was written by Antonio Palomino, the Spanish artist and art historian, in 1724. In a later essay, Palomino is quoted as having written of Pareja as fashioning a new self and another second nature and working behind his master’s back to make his paintings. That almost contemporary writer did not shirk from the fact and found a positive way to acknowledge that Pareja had been enslaved. Pareja was also included by the Frenchman Charles Blanc in his Histoires des peintres (1861-76). We are now recognizing what others knew before us.

Of particular interest for New York and America is the renewed attention paid to Arthur Schomburg, namesake of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library in Harlem. Here, in this series of renewed identities, he is referred to as Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, born in Puerto Rico of a free Black mother from the Danish West Indies and a white Puerto Rican father of Germanic heritage. Schomburg turned into an indefatigable collector of the materials of Black culture and a devotee of Juan de Pareja. His small black and white photographs of his 1926 European trip (partly in search of Pareja) are hung in rooms that open the exhibit at the Met.

This attention to the world and art of Juan de Pareja gives me a new appreciation of Velázquez’s human achievement in making the portrait.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.