Winner of the 2022 ΦΒΚ Award in Science

By Andrea K. Dobson

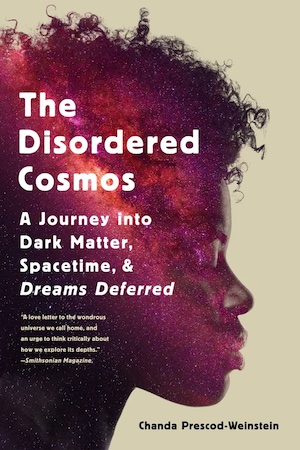

“Once upon a time, there was a universe. We are not sure about how it started or whether there is a reason. We don’t know, for example, if spacetime is ordered or disordered at the smallest scales. . .” Launching us at once into the immensity of the universe and toward its smallest constituents, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein invites us to join her on a dive into the nature of spacetime and the intersection of identity and astrophysics.

As a species, it seems to be a part of our makeup to ask about what’s out there. We’ve looked both by eye (or we did, before light pollution made it impossible for many of us to see the Milky Way spread across our night sky) and with huge telescopes capable of looking far out in space and back in time. For millennia we have also calculated: planets move among the stars, eclipses happen, stars shine, galaxies rotate, the universe is expanding. What equations and principles of physics could explain our observations?

Astro-particle-cosmologist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein asks these questions of the universe at the most fundamental level. In particular, those galaxies rotate so fast that they would fly apart if they were only made of the normal sort of matter that makes up us, the type of matter that we can see when we look at a galaxy. There must be something else, some sort of matter that doesn’t emit or absorb light, to provide the extra mass needed to hold galaxies together. We have, for more than a century now, called this invisible stuff “dark matter”. A dark room can be illuminated by flipping on the light switch, which isn’t the case here; “invisible” or “transparent” matter would make more sense, but the term “dark” has stuck. Prescod-Weinstein asks what sort of particles could provide this extra mass and introduces readers to axions, hypothetical particles that have the right properties and are one of the leading dark matter candidates. She also asks about the implications of using the term “dark” and delves into the physics of melanin and why the work of Black people is so often not seen.

That the term “dark” has stuck with us is just one example of the fact that science is a human endeavor and, as such, is inherently messy, is, in its own way, both ordered and disordered. In addition to particles and cosmology, Prescod-Weinstein is interested in the how and why of the social aspects of science. Who has had a seat at the table – or has been permitted time at the telescope – affects the questions we ask and the uses to which we put the answers. Modern particle physics has been developed by white men; that doesn’t mean that those who aren’t white men aren’t interested in understanding the nature of the universe. Prescod-Weinstein identifies as Black – Jewish – queer – agender and disabled, in chronic pain after being run off the road while riding her bike years ago. She is also passionately interested in understanding the universe and has consistently refused to permit herself to be marginalized in a field that so often has said ‘you don’t belong’.

As a griot, a storyteller, Prescod-Weinstein — who is an Associate Professor of Physics & Astronomy as well as a core faculty member in Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of New Hampshire — seamlessly weaves together her research interests in particle physics and the history of race and science with her own personal narrative and quest for social justice. Disordered Cosmos calls us to care both about the immensity of the cosmos and the structural injustices that have long blocked many from pursuing their passion to understand the universe or from questioning the consequences of the way we do science. Throughout, Prescod-Weinstein holds firmly to the belief that everyone has a right to see, to understand, and to love the night sky.

Andrea K. Dobson (ΦΒΚ Whitman College) is chair of the Astronomy Department at Whitman College.