In the early nineteenth century, public buildings in the United States of America started to be constructed along the lines that epitomized the temples of ancient Greece. This architectural style, which called itself Greek Revival, had become popular in western Europe during the late 1700s and took root in Philadelphia as the century turned. Gideon Shryock, a shy but precocious and ambitious young man from Lexington, Kentucky, journeyed to the City of Brotherly Love in the autumn of 1823 to study with one of the two most prominent proponents of Greek Revival architecture in the United States, William Strickland. After working for a year with Strickland, Shryock returned to Lexington and at the age of twenty-nine won the commission to design a new statehouse for the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Not surprisingly, Shryock drew on his training and presented Kentucky’s legislature with an imposing Greek Revival edifice, which garnered universal praise and established Shryock one of the most influential architects of the rapidly growing western fringes of the United States. The governor of the recently formed Arkansas Territory, who had represented Kentucky in the United States Senate and then been a Kentucky State Senator, invited him to design a meeting hall for the Territorial Assembly. This structure, which adhered even more closely to the classical aesthetic than did the Kentucky statehouse, introduced the Greek Revival style to the lands beyond the Mississippi River and, in the words of Winfrey P. Blackburn and R. Scott Gill, “helped knit—at least architecturally—the expanding United States into an identifiably cohesive fabric.”

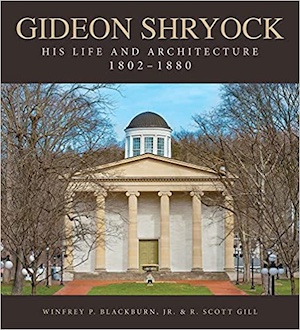

Winfrey P. Blackburn (ΦBK, University of Virginia) and R. Scott Gill’s detailed and lavishly illustrated catalogue of the major buildings designed by Shryock demonstrates the meticulous thought and effort that he devoted to each project. Structures that have been demolished or extensively renovated are depicted as they were originally conceived and built, using a wide variety of drawings, landscape paintings, and maps. Each example is situated in the general atmosphere of the locale in which it appeared: self-confident Lexington, pragmatic Frankfort, frontier Little Rock, and rowdy Louisville. It is hard to imagine that any more can be said concerning the fourteen buildings that the book addresses.

Readers more interested in the overall context of Shryock’s work than in the particularities of each building may wonder what prompted the shift from the original mode of civic architecture in the United States, the so-called Federal style, to the innovative Greek Revival style. The latter is most often presented as an affirmation and celebration of liberal democratic values, particularly in what C. B. MacPherson calls their “possessive individualist” form. Blackburn and Gill suggest that the plans of the Kentucky and Arkansas statehouses also extol the tripartite separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers that lies at the heart of the American conception of democracy.

Yet democratic governance in ancient Greece was open only to a privileged minority, and accompanied an extensive system of slavery. Were the citizens of Kentucky aware of these twin features of classical Greek democracy? And if so, did their adoption of Greek Revival style reflect their intention—conscious or not—to promote democratic rule solely for the propertied (white male) elite of the community? Most intriguing is a short quotation drawn from Henry-Russell Hitchcock and William Seale’s 1976 survey of state capitols, which calls the assembly hall in Little Rock “one of the great monuments of the new Western empire the Jacksonians pledged themselves to possess” (emphasis added). Shryock’s papers and correspondence might well be revisited to see whether his predilection for Greek Revival style accompanied an impulse toward minoritarian republicanism, Jacksonian populism, or manifest destiny imperialism.

In a similar vein, Blackburn and Gill’s study leads readers to wonder why public buildings in the Greek Revival style won acceptance in such a broad range of American communities. Shryock’s designs seem to have been acclaimed just as enthusiastically in highly educated and genteel Lexington as in treacherous and self-absorbed Louisville, “the second city of Kentucky and a cultural backwater among its peers in the nation.” Did Shryock have any thoughts concerning the role of Greek Revival architecture in different kinds of cities? Did he tailor the designs of his buildings to match the societal environments in which they would be erected?

In the spring of 1864, Shryock “undertook what would be his final project on a grand scale,” a massive church for one of Louisville’s three major Methodist congregations. Blackburn and Gill call this building “a marvelous capstone to his long and distinguished career.” But instead of a Greek Revival structure, Shryock created a monumental house of worship modelled on the elegant Chiesa delle Zitelle in Venice, designed by the Italian Renaissance master Andrea Palladio. Shryock removed the dome and upper level of the Zitelle and capped the colonnaded ground level with a Greek pediment. Along the exposed sides he placed “a series of tall, narrow, arched windows reflecting the fashionable German Rundbogenstil—literally ’round arch style’—that had found its way into early American Romanesque Revival architecture.” Did Shryock’s abandonment of Greek Revival style mirror some fundamental change in American culture, perhaps associated with the horrors of the ongoing Civil War? Blackburn and Gill remark simply that the shift marked a “new era of eclecticism [that] left architects without the guiding framework on which they traditionally relied.” Thorough as it is, this impressive volume leaves important analytical questions open for future research.

Fred H. Lawson (ΦBK, Indiana University) is Professor of Government Emeritus of Mills College. Mills is home to the Zeta of California chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.