By Svetlana Alpers

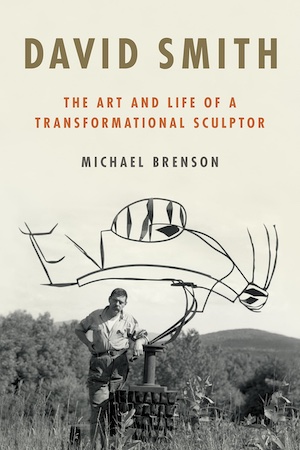

This is an exhaustive, even exhausting, biography. An author who uses words to describe the clothing worn by people in photographs reproduced in the book is giving one a lot to read. But this long, detailed biography of David Smith (1906-1959) a truly great artist or as he thought of himself a great American artist, is well worth the read. Over 800 gripping pages of it.

Though many art-writers are quoted, it is not itself a critical study. And indeed readers who have previous knowledge of the look of Smith’s works will find the going easier. The publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux is not good with illustrations. I shall not be offering descriptions here, but one hopes readers at least have an image in mind of the many and various figures of welded steel “personages,” as they were called, with which he populated his fields in northern New York state. As John Chamberlain, the sculptor, extravagantly exclaimed, “When I saw David Smith’s work, it didn’t remind me of anything, and that was the key. It was like America, we have risen.”

What is the point of the biography of an artist? It depends on the artist. In the case of Picasso, John Richardson correctly, I think, took the view that people Picasso used as subjects, often lovers and wives, were central to his styles of making art. This has been disputed as falsely turning art into biography. But of Picasso, it seems a truth. (These days he is criticized by some for the presentation in his art of those he was involved with.)

David Smith is different. Brenson effectively offers a history of the (mostly artistic) times through Smith’s life and art-making. In a sense his life and art give us an angle on the time. A remarkable aspect of Smith’s sculpture is that it looks so contemporary. In the telling, the same seems true of his life and times. Dorothy Dehner, Smith’s first wife (1927-52) an artist herself, supported him. Jean Freas, his second wife (1953-58), the mother of his two (beloved) daughters, took him to court for money from the time of their divorce until the end of his life. The evidence is that Smith was highly intelligent, could be charming but over-bearing, and toward the end he drank too much and went after younger women with little success. He did not make use of them in his art as Picasso had done.

Smith was born in a rural, developing Decator, Indiana. On his own account (he always used words with force and care), he grew up amidst trains and factories. As he said to the English critic David Sylvester in 1960 about being an American, “I also like the idea that we have no history—that we have no art history and pay no attention to art historians and that we’re free.” Continuing the theme, he spoke of the new, large American abstract paintings as “a statement of freedom, a statement of liberty.” For a lifetime, factories were by way of serving him as workplace and studio. After briefly working at Studebaker in South Bend (1925), he had working space at the resoundingly named Terminal Iron Works in Brooklyn (1933) and then, moving on from gas to arc (electricity) welding in 1942, worked as part of the war-effort at ALCO (American Aluminum Co.) in Schenectady, New York. His commitment to workers and labor was under pressure there, but it never swerved.

He had escaped to New York in 1926 and briefly went to the Art Students League to study painting that, turned sculptor, he never left behind. A distinctive (but also sometimes fleeting) aspect of his welded works is that Smith applied paint to their surfaces. Things happened thick and fast: married in 1927; to the Virgin Islands for 9 months where he picked up driftwood and other discards, and started to photograph; in 1929 his wife’s money bought land at Bolton Landing in the Adirondacks, which Smith called home from 1940 and in whose fields he installed sculptural works as a pointed alternative to the museums and galleries of the capitalist art system that he fought.

He also opposed the supremacy of Western art and culture. Smith’s taste in art was expansive long before the current interest in what is referred to as global art. In the darkening 1930s, the couple went to Europe—France and Greece and Russia. Everywhere, Smith attracted people of interest and use for his work—the originally Russian, French-speaking artist John Graham a friend in New York, in Paris the great French critic-collector-gallerist Felix Fenéon who fed Smith’s taste for primitive art (as it was called).

He also attracted fine critics—famously Clement Greenberg (who in 1942 wrote “Smith is thirty-six. If he is able to maintain the level set . . .he has a chance of becoming one of the greatest of all American artists”). But also surprising to me here are superb words by Fairfield Porter and Frank O’Hara. I did not know either of them as writers about art at such a discriminating level.

Smith is an artist who is difficult to get to see and therefore difficult to get know. He was dead set against producing multiples. (Think Degas’s Little Dancer and the legal tussles over the originality of many Rodins). With the exception of his bravely titled Medallions for Dishonor—a set of which can be appropriately viewed today in the Madrid Reina Sofia near Picasso’s Guernica—Smith made unique works that he often produced as part of titled series.

Smith swore by America and being an American. But he was a man open to his own contradictions. He was open to the larger world. One of his most stunning series was produced in 1962 at the Voltri factory in Genoa, Italy, for display at the festival in the town of Spoleto. There he was not at home in America, but at home in a welcoming factory.

Brenson has written the life of David Smith in all its fullness, without passing judgment. The book will leave readers, as it has left me, with a lot to think about.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.