By Svetlana Alpers

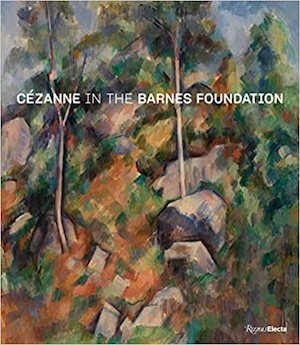

This is an essential book for those who value Cézanne, and an ideal presentation of the artist for everyone else. It is a beautifully illustrated, well-conceived presentation of the sixty-one oil paintings and eight works on paper, once in Merion, Pennsylvania, now in Philadelphia, collected between 1912 and 1939 by Albert C. Barnes. The heavy volume (I rested it on a table to read and look) arranges the pictures by date of making but flexibly enough to group together recurring motifs (e.g. still-life, bathers). It seems that the authors were given free rein, making some of the cluster essays with numerous illustrations a bit hard to follow. At the end there is a useful list by date of purchase. You learn about Cézanne but also about a collection. And a collection that, because for so long it never travelled, remained largely unknown. There is a whiff of apology expressed about the fact that Barnes collected with teaching (and publishing) his understanding of art in mind. But is collecting simply to possess better?

It was an unusual advantage for conservators, that so many paintings could be studied in one place as is not possible in large exhibits normally created through loans. The introductory Materials and Techniques section (and its images) is superb. Here, as in the later comments on individual works, it is an example of keeping to their knowledge and skills and not ranging out into interpretation as conservators often (I think unnecessarily) do these days. One learns that in addition to leaving canvas unpainted Cézanne scraped away paint to make it bare, that his use of initial drawings on canvas is inconsistent, that he added on pieces of canvas while working, that in portraits the absence of white in the eyes makes for the mask-like faces, and that the unfinished look of fingers is surely not to suggest movement (as suggested here) but because painting hands was particularly challenging for Cézanne.

The catalogue essays expose a range of critical writing on Cézanne today—from interest in the circumstances of the Provençal land that was essential for him, to pictorial influences (but is it necessary to demonstrate by train schedules from Aix to Montpelier that Cézanne could have travelled to see a particular Ingres), to run-on descriptions of brushstrokes (but can language be made to catch the painter in the act) to psychological imaginings (but do the women bathers show the “inescapable baseness at the core of human nature”).

I have a general memory of the Cézannes at the Barnes (which are not hung together) as being a mixed bag—there are great paintings like The Large Bathers (1900-1906) and The Card Players (1894-1895) and certain small still lives, and also many that are not great. A painter friend of mine remembers that many of the paintings are overly finished. I would cite, for example, the two disappointing paintings of the Bibémus Quarry (cat. nos. 35 and 36) that are not addressed in their catalogue entry, which is largely on Cézanne’s Provence. While there is an interesting essay by John Elderfield on Barnes’s 1939 book on Cézanne, there is no direct consideration of the whole collection as it finally ended up (some works were bought and then sold).

Finish has been a continuing concern on the part of writers and viewers of Cézanne. What sense do we make of so much canvas left unpainted? See for example the stunningly thoughtful view of a town, cat. no. 30 (described here as remaining unfinished) compared to the burnished view of another town, cat. no. 29. An essay by Carol Armstrong addresses the question head on to conclude with Merleau–Ponty, the author of Cezanne’s Doubt, that for Cézanne to succeed meant to be able to risk failure. But is it not so that it is of the nature of painting (as contrasted with the writing of a poem) that the artist often does not finish, but rather simply stops (abandon may be too strong a word) then to start all over again. This takes a particular form with Cezanne, but is it not true of painting in general?

The writers generally avoid the art historical habit (for that is what it is) of considering form and motif (and iconography) separately from each other. Though the frequent reference to Cézanne as anti-illusionistic or not following one point perspective is worth noting. Addressing this in the late Joseph J. Rishel’s catalogue entry for The River Bend (the earliest work in the collection and Barnes’s final Cézanne purchase) we read, “Cézanne was . . . perhaps the first man in history, to realize the necessity from the way the paint is handled to build up a homogenous and consistent pictorial structure . . . [discovering] an intrinsic structure inherent in the medium and in the material.” The words were written by the English painter and critic Lawrence Gowing. Curiously they are not indexed, and indeed, surprisingly, I think this is the only reference to that great writer on Cézanne in the entire volume. Perhaps there is an explanation.

Except under pressure, and indeed by accident, Barnes took no interest in Cézanne’s drawings—an interest in which was slowly bubbling up in the 1930s. Though separate from the making of his paintings, Cézanne’s many drawings and watercolors were essential to his seeing and to his imagining—as is magnificently visible in a recent exhibition at MoMA. Gowing wrote intently and perceptively about that. Gowing’s unfortunate absence has perhaps to do with the absence in Barnes himself, and in his collection, of an interest in the man making.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.