By Svetlana Alpers

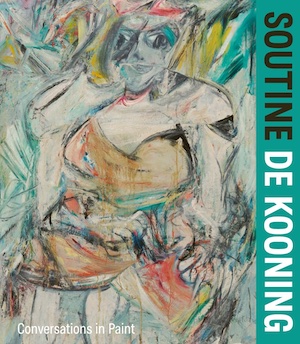

You have until August 8 to get The Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia to see the exhibition of paintings by Chaim Soutine and Willem de Kooning introduced and documented in this fine catalogue. Beginning with educational essays, the book reproduces all the works exhibited (ending with images of the other Soutines still in the Barnes) and includes not only the expected chronology, but also a telling assemblage of relevant critical texts. The book is to hold and keep, but if you live within reach, the show is one not to miss.

After I drove down from New York to see it in March, I excitedly jotted down the following notes. The Soutine/de Kooning exhibition show is a lesson in or, better put, an experience of painting. Undogmatic in its layout, generous in what it shows. It opens aggressively and suggestively with a 1921 View of the Village of Soutine hanging on the wall to the right of the1955 Composition by de Kooning (plates 31/ 32 in the book): Soutine, a fatal tumble of houses, trees, with a small figure, and de Kooning a density of marks with signification uncertain. The Soutine landscapes, not all but most, are particularly fine—dense, turbulent. Not expressive turbulence, rather paint turbulence. Surprisingly, de Kooning’s aggressive working of the paint comes out as a bit slap-happy compared to the dark tragedy of Soutine. One discovers that de Kooning could not paint the human face, never (while Soutine could!). His early faces look soft and pretty (like John Graham). Effectively, de Kooning simply displaces the face somewhere else to avoid it. The pink in de Kooning is female flesh, the pink (no, red) in Soutine is a flayed animal. Anyhow, wondrous, really wondrous.

There is a back story to the exhibition: on being shown Soutines in Paris in the early 1920s, Albert Barnes, out of love and also as speculation, bought 52 on the spot—making a new life possible for the impoverished Soutine (1893-1943). De Kooning (1904-1997) came upon Soutine exhibited frequently in New York in the 30s and 40s. MoMA put on a retrospective in 1950. In 1952, with his wife Elaine, de Kooning went to the Barnes Foundation to look. Interviewed in 1977 he stated, “I’ve always been crazy about Soutine.”

So what is to be made of the relationship in America, as it were, between these two European- born and trained painters ? A reviewer of this exhibit questioned whether indeed Soutine had a profound influence on de Kooning. But Conversations, the subtitle chosen for the exhibition and the book, is equivocal about that. You can see similarities, yes. The notion seems to be to get people to look and judge for themselves. Both artists, Europeans in that sense, revered the art of the European past, the art of museums. That conservative aspect of de Kooning (like that of Soutine) angered Clement Greenberg, the discriminating critic and leading advocate for New York abstraction. He turned on de Kooning for his return to figuration.

De Kooning’s reputation became firmly established. Soutine’s was often challenged or at least it is fair to say his painting has been seen as deeply disturbing. It is bracing, in the view of this exhibition and book, to read the frank 1937 words of Henry McBride, a too often overlooked twentieth century art critic writing in New York from the 1910s until the 1950s. (Why is he not quoted in the book?):

“It seems natural to begin an acquaintance with Soutine with a profound distaste for him . . . . Surely there never was a more crabbed—I believe that’s the word the gypsies used to describe the quality—artist since the world began, and he is so contorted and twisted in his procedures that I shouldn’t be surprised to have him turn out to be a gypsy in the end . . . . But that does not prevent him from being a very great painter just the same.”

So what was Soutine to de Kooning? A Dutch painter of my acquaintance who is passionate about de Kooning suggested that the power of seeing the two together might be to see what de Kooning saw he himself was not able to do in painting. It is precisely Soutine’s devotion to figuration (meaning broadly the traditional genres of landscape, portrait, and still- life) that de Kooning longed to continue. In a way, then, Greenberg was right that de Kooning was a conservative. But was he also a disappointed one?

So, with this book to hand, go to Philadelphia before August 8 and see for yourself—or failing that, get to the l’Orangerie in Paris. It is the second venue of this exhibition from September 15, 2021 to January 20, 2022, perhaps because the second major collector of Soutine was Paul Guillaume whose collection is found there.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.