By Svetlana Alpers

Paul Binski’s book on Gothic sculpture is as fascinating to look at as it is to read. Published as a joint project by the Paul Mellon Centre and Yale University Press, London, it is dense in seeings and arguments, and is superbly illustrated. The effect is to make strange those impressive portals and stunning sculpted figures that we modern travelers in France, Germany, and England have come to admire almost casually. It is a turning away from the many art historians who have plumbed them for meanings and responded to them with misplaced empathy. The book alters the way one sees and, if I may put it that way, thinks Gothic sculpture.

Binski begins with stone and portals. These are seen not as a passage through (in other words not as liminal in the anthropological sense), but as a setting forth. Rather than engaging us in an empathetic response, a portal calls attention to a moral predicament. In Binski’s words a great portal is not an enchantment, but an engagement.

When we look at a Gothic Last Judgment portal, it is hard for us not to see and feel fear for the damned and joy for the saved. On this account, however, that was not the impulse of the original making or viewing. Our view superimposes a personalized, romantic view on something quite different. Binski offers the evidence of the verbal record (apparently unique) of St. Hugh guiding King John around such a portal. Seeing a portal does not involve self-knowledge because it is rather a demonstrative experience or, in rhetorical terms, epideictic. It is intended to bring about conviction and action, in this instance a prayer for forgiveness.

Reason, in this scheme of art, is not separate from the emotions but guides them. Unlike the passing feelings we may have as separate individuals, what is in play is cognition, which has a common social basis. Such art assumes self-regulation rather than self-expression. Binski takes us back to a medieval valuing of constraint, singling out those rare art historians who have scrupulously attended to things as they were rather than, as so many estimable scholars seem to have done in modern times, as they feel them to be.

It is interesting to find renewed attention given to the common modern view—the privileging of the individual and the march of progress towards that— of a line of impressive thinkers and writers such as Erich Auerbach, Erwin Panofsky, Meyer Schapiro, Carolyn Walker Bynum, and Hans Belting. Time passes, and the initial pleasure of reading texts by those impressive writers may fade. It is bracing to have their (admittedly diverse) appeals to freedom of self and class reviewed and then questioned by the particular conditions of medieval art put forth here. Sculpture is not an object of human fantasies. It proposes cognition not emotional self- examination. It values constraint not freedom. It places a “we” before an “I”.

The frequent illustrations are placed so as to articulate the accompanying text. In fact one can view them independently as a kind of continuous proof for the eye as Binski’s words strive to demonstrate the medieval way to think and look.

Moving on from Stone (part one) to Wood (part two) we enter into the church. Having challenged human experience as entertained by recent viewers of medieval art (as in the notion of a portal as liminal), Binski challenges the anthropological turn (the commanding name here is Alfred Gell) for a second reason. Considering artifacts as lived experience—effectively considering art as material substitution rather than as representation—is to deny their aesthetic nature.

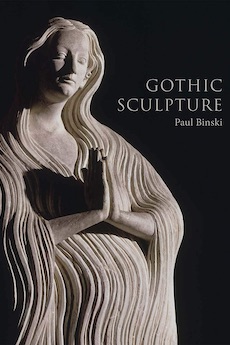

The argument, for the aesthetic status of medieval art, is strongly made, and it is an important one. The magnificently worked hair-become-undulating-body of the penitent Magdalene displayed on the front cover says it all. (Though confusingly, this great limestone figure is presented in the section titled Wood!). A thinking through of the beauty of this sinning woman (go back to the sinned and the saved on a portal of the Last Judgment) is what was intended. Illusion, we come to understand, was not uniquely the revolutionary purview of the Renaissance.

This book makes one realize, or is it makes one conclude, that the definition of Renaissance art dependent on its difference from medieval has been misleading. Misleading, as Binski shows, for the making and viewing of Gothic sculpture, but perhaps also for the making and viewing of the art of the Renaissance.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.