By Svetlana Alpers

This is the third of a trilogy of riveting biographies written by Cathy Curtis on American women painters. Grace Hartigan her first, Elaine de Kooning her second, and now Nell Blaine were all born around 1920 and came into their own in the New York of the 1940s and 1950s. They lived at the center of a then small world of painters and poets and critics. As Curtis shows, each had marked success in her lifetime. That success is striking to read about just now in the current rush to give women artists equal place in public attention and collections. Were things better for women back then? If so, what happened?

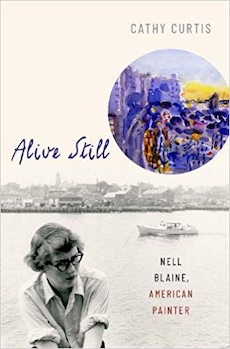

While Hartigan and de Kooning in different ways remained well known, Blaine has been rather forgotten. Mary Gabriel’s acclaimed 2018 Ninth Street Women gives generous accounts of Hartigan and de Kooning but mentions Blaine very much in passing. Curtis’ account of Blaine’s life and work rectifies that not through hagiography—the Blaine presented here is hardly an easy person to like—but through trying to show how it was. She adjusts the texture of her writing style and address to the artist, which means here to what might be called the locomotive details of a life. For the challenge Blaine faced was physical paralysis. When she was 39 she was struck down and paralyzed by polio while on vacation in Greece.

Blaine had started in an abstract mode and studied happily, as did so many others, with Hans Hofmann. An early abstraction has a whiff of Stuart Davis about it. Blaine was into jazz. She married and divorced and had multiple lovers, both male and female, before she settled into the choice of women. Curtis speaks of the choice with ease, making no more if it in telling the life than Blaine did in the living of it (at least that is Curtis’ take). That was simply how it, or rather she, was. Again, perhaps, a contrast to our times.

Before polio struck her down, she was chosen for exhibitions and written about by such as Clement Greenberg, Meyer Schapiro, Tom Hess, and Leo Steinberg. She had been invited to Yaddo and also to the MacDowell Colony. After polio, her style having morphed from abstraction to landscape and still life, things went on much the same. Having accepted that she would never stand or walk again, she found ways to use both her hands (the left for painting, the right for watercolor) and to go on with her painting.

With devoted lovers, companions and paid helpers, she lives in a large apartment on Riverside Drive, travels widely, buys a summer house in Gloucester, and lives a while in an inherited one in the Austrian Tyrol. Curtis’ telling of it uncovers the tensions, frustrations, and planning that went on behind the scenes in order for a woman and artist as physically challenged as Blaine to go on almost normally, one might say. The same tenacity and ambition that had got her somewhere in her painting also kept her going in her life. Alive still indeed.

But Curtis, an art historian by training and a critic by career, is also, and this is true of all her biographies, attentive to art. She takes the time to place Blaine’s work among other Gloucester painters, and others concerned with still life. I must admit that I find that the coloristic and to my eyes too brisk, even mushy manner of representation does not attract. But what is striking is how many leading critics of the time thought her paintings were very fine. She had exhibitions almost every other year, and the Fischbach Nell Blaine exhibition of March-April 1985 sold 35 works.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.