By Allen D. Boyer

“On March 2 and 3, 1859, Pierce Mease Butler of the Butler Plantation estates in the Georgia Sea Islands sold 436 men, women, and children, including 30 babies, to buyers and speculators from New York to Louisiana. It was the largest recorded slave auction in U.S. history. . . [and] netted $303,850 for the debt-ridden Butler, a phenomenal sum.”

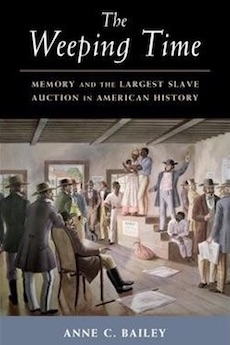

Held at a Savannah racetrack, the distress sale was covered by a reporter for Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune. Anne C. Bailey, a SUNY Binghamton historian, unlocks the story, offering a microhistory of Sea Islands slavery and a study in collective memory. Slavery and debt equals labor and capital. Toni Morrison is hailed in the acknowledgements, while Eugene Genovese is absent from the bibliography, but The Weeping Time delves deeply into costs and values and how plantation work and Gullah culture shaped each other.

Butler was selling slaves because he had lost money in the stock market. The slaves were arbitrarily paying for someone else’s misjudgment. Ironic mercies fell randomly upon a few. One young couple married on the way to the auction block and were bought together, departing for a plantation in Alabama. A mother holding a newborn baby asked Butler if her family could stay on their home island and not be sold; Butler pulled them out of the offering queue. The gesture was capricious, but it was not empty chivalry; by foregoing this sale, Butler gave up the $4,000 that the family would have brought him.

More often, the ironies were unhappy. One young cotton hand persuaded the man who bought him to bid for his sweetheart, due to be sold the next day. However, when the moment came, his new master did not put in a bid; the young woman was offered as part of a lot alongside four other rice hands, laborers he did not need.

Six years after the auction, when freedom came, some of the slaves whom Butler had sold made their way back home. However, they worked for wages now, and they refused to dig ditches, the best-hated part of rice planting. Their masters complained that freedom had made them shiftless—which really means, as Bailey notes, that they would work only on the terms that they chose.

Bailey traces the history of black families caught up in the Butler auction. Some young field hands escaped slavery and saw wartime service in the United States Colored Infantry. Little children sold in 1859 grew up to be ministers and laundresses and homeowners and railroad men. People once described by nicknames and occupations and lot numbers (“Chattel 105, Commodore Bob, aged, rice hand”) acquired surnames.

How these free people defined themselves is a twofold study—in the varied tricks that memory can play, in how identity takes shape. Some who were auctioned off seem to have held no grudges, while others recalled injustice. Six families who passed through the auction later took the name of Butler. By contrast, Margaret and her husband Doctor George, the family whom Butler withdrew from sale, made a clean break; they took the name of Goulding. The common factor is that, possessing freedom, they chose for themselves how they would be known. For them, Bailey concludes, “the auction block neither erased [their] history nor eradicated the future. The auction block that once represented a time of weeping can now represent a new era of recovery and restoration.”

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University, 1977), a lawyer and writer in New York City, is the author of Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Age. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.