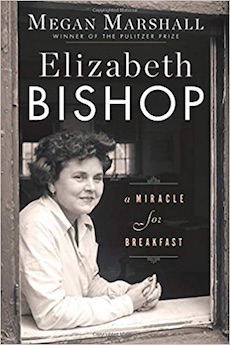

Shortlisted for the 2018 Christian Gauss Award

By Lewis Fried

Elizabeth Bishop is authoritative and lucid, drawing upon recently discovered material and interviews. It also is a “dual” study of Elizabeth Bishop’s life as well as Megan Marshall’s. When the two are analogous, Marshall conveys a common struggle: the search for recognition, a deep loneliness, a marriage for one that failed, relationships for the other that fell apart, and a shared triumph (the acclaim for creativity).

The book begins with an epigraph, written by Gamliel Bradford, guiding both the form and sensibility of the work while revealing its author’s attraction to her subject. In Bradford’s words (and I do not quote the entirety of his observation), “Every human being is a biographer from childhood, in that he perpetually…detects with keen and curious thought the resemblances and differences between those souls and that…more puzzling entity, his own, and weighs…the bearing and effect of others’ thoughts and actions upon his own life.” As Marshall’s interest in Bishop’s work increases, so does Elizabeth Bishop force us to ask if there is any “disinterested” biography that can afford to understate the binding of reader to writer?

A gifted scholar who was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for her Margaret Fuller, Marshall was not an intimate of Bishop’s, but she was her student. She had been accepted into a class led by Robert Lowell, but because of his nervous breakdown (one of many), Bishop took over on “three days’ notice.” Unlike many workshop professors, Bishop encouraged, if not disciplined her class, in the craft of rhyme, and poetic form. Among the most arresting parts of this book are the detailing of what Bishop insisted was important in her pedagogy of poetry—certainly displayed in her own work—and a memoir, both sentimental and thankful. As a result, we get a hands-on account of Bishop’s instruction, as well as a student’s responses, for example, when one of her poems missed the mark (an episode that also haunted Bishop).That Marshall’s disappointment plays a significant moment in her account indicates the importance, if not awe, she attributed to Bishop. (Although this strikes me as an overly-sensitive student’s response, almost that of an adolescent’s, it illuminates the respect and recognition she desired from her teacher, perhaps akin to Bishop’s early reliance on Marianne Moore’s commentary.)

Bishop’s life was scarred and, ironically her poetry, at times, strengthened by her tribulations and environments. Her childhood was pockmarked by illness, by molestation, by death, by the madness of her mother, and often by passionate, failed love affairs. Apparently timid by nature, she had difficulty thriving in the public atmosphere of awards, and the assertion of her successes. Moreover, as a lesbian who lived in an unwelcoming environment, her quest for emotional security, often fractured by her drinking, led her to shy away from a glaring display of affection, and her public poems to conceal her sexual identity. Amongst the company of prolific writers, such as Robert Lowell, she berated herself for falling behind, for being unproductive. And yet, her poetry, with its tight prosody and form, with its luminosity and depth, fulfilled Yeats’ dictum that poets must learn their “trade.” And she certainly did.

Her travels, voluminous reading, and her sojourns in places such as Key West and Brazil took her out of her provincial childhood making her subjects specific yet placed within a synoptic vision encompassing “perennial” questions. Sometimes sunk in a locale, their import was universal. (Most startlingly, her richest work, in this reader’s estimation, “The Riverman,” portrays for an American, the recognition of another way of knowing: of shaman, myth, and individual as the subject descends into and swims a river. It finally doesn’t matter which one; the poem’s strength draws upon a foundational myth’s reliance on the descent and ascent into a world previously hidden and an individual rebirth. It also indicates the need for myth—to an American poet—when accounting for the sheer affluence of experience.) Another salient example is “At the Fishhouses,” taking us from a locale to the universal problem of what “we imagine knowledge to be.”

Marshall’s biography nicely ties the “places” of Bishop’s life to the expansion of her themes. For example, Key West , this once-isolated and easy-going town, now with its growing naval and air fleet, made the coming of the Second World War a present and violent terror, finding its place in the allegorical “Roosters.” Her years in Brazil sharpened her sense of being an outsider, a spectator, and as such “fired her imagination”; Rio’s sharp contrast between those who lived in luxury and those inhabiting the favelas could only have reminded her that her life was “born of such an imbalance.”

Sadly, her last years in Boston, teaching gifted and exciting students, also signaled the end of a vibrant life: her great friend, Cal Lowell, had died; her drinking did not get better; her productivity did not increase. Nevertheless, her ever-present demon, the sense of falling behind was belied by her accomplishments. Her reputation, marked by an enlarging readership, grew well after death. She was no longer (even if she had believed it) someone struggling to find a place in the domain of letters. Her art had rescued her. “Poetry,” Marshall writes, “had been her refuge, her escape—had ‘freed’ her.” May we read her in the security that she now has achieved, but believed had eluded her.

Lewis Fried (ΦBK, Queen’s College, CUNY, 1964) is Professor of English Emeritus at Kent State University and a resident member of the Nu of Ohio Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.