By Allen D. Boyer

The bloodiest day of the American Civil War—a battle bloodier than Pearl Harbor or the attacks of September 11th—was fought in the autumn of 1862, in Maryland farmland rich with corn, on the hills above Antietam Creek. At Antietam, more than 3,500 Union and Confederate soldiers died, cut down by rifle fire, by grapeshot, by bayonet and butt-stroke. As a white-haired general staggered with a mortal wound, a young Maine lieutenant realized that this was no ordinary battle—“how mighty easy it was to get killed or wounded that day.”

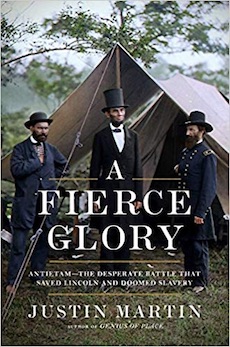

Justin Martin, who wrote the award-winning biography Rebel Souls: Walt Whitman and America’s First Bohemians (2014), has produced an arresting account of Antietam. He writes with the colloquial tone of a battlefield guide—and, like a battlefield guide, provides expert knowledge of that engagement’s terrain and tactics.

A correspondent for the New-York Tribune called Antietam “the greatest fight since Waterloo.” The musketry was a ceaseless din, remembered as the sound of “rapid pouring of shot upon a tinpan, or the tearing of heavy canvas.” Before rushing the narrow stone arch of the Rohrbach Bridge, the 51st Pennsylvania Regiment demanded that their whiskey ration be restored; it was. The Georgia infantrymen defending the bridge (450 strong, they had held off twelve thousand) had fired off all their ammunition; they had bruised black-and-blue shoulders.

Two generals dominate this history. One is Union commander George B. McClellan, who had fortified Washington and trained the Army of the Potomac—the “Young Napoleon,” clever, ambitious, high-strung, and anxious. He was fond of his troops and reluctant to risk them. Facing McClellan was Robert E. Lee—a stern monolith of a general, older than McClellan, but nimbler and more pugnacious. Unlike McClellan, Lee made ready use of his soldiers. When the fighting at Antietam hung in the balance, Lee’s youngest son, an artillery officer, asked his father if his battered cannon and caissons were going back into the fight; Lee unflinchingly ordered them back.

Behind Lee and McClellan, a more monumental presence overshadows this book: Abraham Lincoln. Looking beyond the battlefield, where Confederate forces fought Union troops to a standstill, Martin emphasizes the different way in which Antietam proved a turning point of the war.

By September 1862, after more than 18 months, the Union government had been unable to suppress the rebellion. A recent run of Confederate victories (at Second Manassas, in the Seven Days fighting on the Peninsula, at Harpers Ferry) had disheartened Republican voters, which threatened Lincoln’s support in Congress. It seemed likely that Britain would intervene, “offering mediation”—which meant, peace talks and Southern independence.

“Over the summer of 1862, during that series of Union setbacks,” Martin writes, “the president began to weigh a new option. “Amid so much pain and sacrifice, something was desperately needed to kindle a fresh Northern commitment to the war effort . . . . Lincoln called a meeting of his cabinet. With all seven members assembled, he revealed his plan to issue an emancipation proclamation.” Secretary of State William Seward, a canny man, suggested that Lincoln issue the proclamation after a Union victory. Lincoln wrote out a draft proclamation, put it aside, and waited for a victory.

When Lee’s army fell back across the Potomac, Lincoln decided that Antietam had been a victory. He issued a proclamation that changed a war to save the Union into a war to free the slaves. Sir Winston Churchill, who understood both war and politics, might have called Antietam the end of the beginning of the Civil War.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University), a lawyer and writer in New York City, is the author of Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Age (2003). Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.