Jay M. Pasachoff

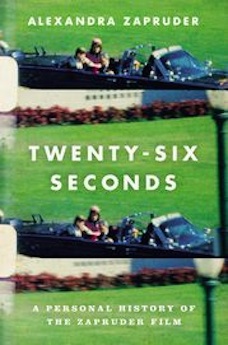

Alexandra Zapruder has written a strangely fascinating book. Those of a certain age will recognize the name Abraham Zapruder as that of the amateur photographer who took the unique movie footage showing the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in his limousine as it drove down a Dallas street. His granddaughter has brought the family lore together with exhaustive research to provide a very readable history of the film, its handling, its copyright, its relation to the Warren Commission and other investigations into the assassination, and its legacy.

Though it may seem obvious at a moment’s thought, the Zapruder film is not the assassination itself, as much as some of those trying to get access to it claimed they should have it because of the importance of the event. Abraham Zapruder, immediately realizing the importance of what he had photographed on his movie camera, held off gaggles of newspaper reporters trying to get his film, insisting that it go first to the Secret Service. In fact, he almost alone for a long time among the general public knew that the President was dead, since he had seen the devastation of the second bullet—while those of us waiting around the country on November 22, 1963, for updated news had hope for Kennedy’s survival since we knew he had been taken to Parkland Hospital.

Zapruder’s care that his film not be sensationalized, especially by not showing the most graphic of the frames, led to his turning it over to LIFE Magazine, then an outlet of incredible influence and high reputation, led to decades of care and of fending off many permission-seekers. Eventually, the burden seemed so great that LIFE returned the film to the family, and Henry Zapruder, the author’s father, took over the role of naysayer and sometimes permission-granter on top of his legal practice.

Alexandra Zapruder—who points out that the family’s name is so unusual that it sticks in your mind, unlike, say, Cohen would have—covers many of the controversies including the assassination and the role of Lee Harvey Oswald, who was held by the official US inquiry (the Commission led by the Chief Justice of the United States, Earl Warren) as the sole shooter. We learn of “magic bullet” theories, and how the physicist Luis Alvarez worked out the physics to show that the backward thrust of JFK’s head following its forward jerk matched Newton’s third law based on what Zapruder photographed, and didn’t prove that there was a second gunman, on the “grassy knoll” of legend or elsewhere.

For those of us who were alive and old enough then to be cognizant of the event, Dallas and the name Zapruder are almost synonymous. Indeed, following the January 2017 meeting of the American Astronomical Society just outside Dallas, I am planning to make my first-ever trip to Dallas proper (and not just DFW airport), with a visit to the “Sixth Floor Museum” in the old Texas Book Depository Building scheduled with the Williams College students who will be with me on our winter-term travel course. (I had learned decades ago, as a junior-high-school science textbook author with my wife, Naomi Pasachoff, that Texas was one of the rare states that had central purchasing of school textbooks, leading to there being a centralized depository.) We learn in the Epilogue that the Zapruder family has, after decades of complications, donated the copyright to that museum.

Ms. Zapruder’s book will find a place on my syllabus the next time I teach my undergraduate course on Science and Pseudoscience. She raises all kinds of interesting and philosophical issues on the nature of imaging, on standards of proof, and on private vs. public. I have been boycotting the films of Oliver Stone since I had read what he did in the movie JFK to invent controversy when there was no real one. Ms. Zapruder takes up the movie and its point of view, as well as the actual prosecution (persecution) of the businessman Clay Shaw by the New Orleans DA. Every time now that I see a docudrama, I wonder what is real and what is not—and “fake news” has even proven significant for the 2016 presidential election. I’ve been enjoying the weekly TV CBS drama Madame Secretary and how this enlightened Secretary of State gets us and her president out of worldwide difficulties—but now I worry that the made-up world crises may get stuck in my mind, much less in the minds of less knowledgeable people.

What about off-the-wall artistic use of the film? The artists “had to do something wildly inappropriate, radial, even taboo…. ‘Our need was to break down that wall…with the belief that the cracks would widen and other ‘hidden truths’ would reveal themselves.'”

Or requests from the general public: “I would like very much to have a copy of the Zapruder film and not, I repeat not, because of the graphic depiction of Kennedy’s wounds but because the Zapruder film may very well be the most important piece of historical film taken in the last 20 years.”

Or real literature: The author even had lunch with the reclusive Don DeLillo. In his 1997 book Underworld, DeLillo’s characters attend an art installation at which the Zapruder film is showing, and “DeLillo conjured up a scene that suggests the film’s meaning not only in the context of 1974 but also in the enduring present.”

Alexandra Zapruder’s book Twenty-Six Seconds is fascinating to read and gives much food for thought. I heartily recommend it to people of all adult ages, to those survivors of the Kennedy years for their memories and to younger people for their enlightenment.

Note: Alexandra Zapruder had an interesting and relevant Op-Ed on conspiracy theories in The New York Times: http://nyti.ms/2hxZaYk

Astronomer and author Jay M. Pasachoff is the director of the Hopkins Observatory and Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College. He is a Visitor in the Planetary Sciences Department of Caltech. Williams College is home to the Gamma of Massachusetts Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.