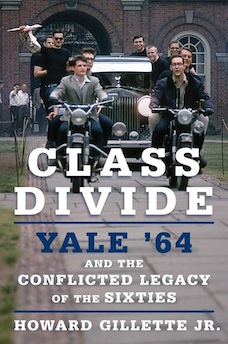

By David Madden

The legacy of the 1960s may well be fresher in the minds of twenty-year-olds in 2016 than the Civil War of the 1860s was to the young in 1916. Howard Gillette’s focus on one hundred graduates of Yale’s class of ’64 provides another wide, multifaceted view of that decade—a decade we do well to revisit for contrast as we ponder ways to understand the on-going, extremely different and puzzling student behaviors, evolving convictions, and protests in higher education.

A member of the class of ‘64 who served as managing editor of Yale Daily News, Gillette begins with a comparison between the traditional type of Yale undergraduate and the already quite different freshmen of 1960, who developed as young adults of that troubled decade into new conservatives and new liberals. They arrived at Yale as the Age of Conformity was fading and as the Age of Anxiety was setting in and graduated into the Age of Protest. Members of the divided class of ‘64 became engaged in all the issues of the decade, including politics, the environment, student protests, marriage and family, the cold war, military service, Vietnam, affirmative action, capitalism, women’s rights, religion, civil rights, civil liberties, countercultural experiences, personal freedoms, sexuality, and even philanthropy.

Gillette brings his readers up-to-date on his classmates’ lives, not only the now famous ones, the Jewish Democrat Joe Lieberman and the waspish Republican John Ashcroft. “No member of the class of 1964 better exemplified membership in the modern meritocracy or the determination to reconcile the clashing perspectives that emerged from the 1960s than Joe Lieberman.” Gillette tells the stories of the not so famous ones, as well, including an extended narrative of the benighted civil rights activist Stephen Bingham, the environmental activist Gus Speth, and the humanities professor Stephen Greenblatt. Gillette himself went on to head the “moderate” Republican Ripon Society in the early 1970s, to teach at Rutgers, and to write three books on what urban communities are and should be.

Like too many on both the right and the left these days, Gillette makes exaggerated claims, as if not trusting the full weight of his thesis, invoking the old “yes, but…” response. For instance, he agrees with other commentators who say that the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in the fall of 1964 marked the onset of the “upheaval that permanently rocked American culture,” that would help “redefine American life. Their origins can be found even in the intuitively unlikely locus of a group of Ivy League students entering the 1960s.” At the end of the “long sixties,” “this class that once looked so homogenous was already divided in ways that only the 1960s could explain.” He goes on to claim, “No doubt, the shift from grand to diminished expectations for self and country was part of a greater disillusionment that attended the culmination of nearly a decade of polarizing politics and policy.” Gillette also asserts that it is “impossible to deny that the members of the class of 1964 are part of a ruling elite, albeit one that has experienced tensions between equality and privilege, convenience and social responsibility, rebellion and convention.”

Class Divide is then one of those books that begins with a great notion that proves to be too limited for a book. The writer of such a book may become aware of that limitation but forges ahead anyway, convincing himself that what is merely relevant is germane. Gillette wanders away now and then—though quite interestingly—from his focus on individual members of the class of ‘64 to describe in great detail the general history of the issues he has posed and their legacy. He forcibly yokes together two related but different stories: the Yale class of ‘64 and the Sixties itself.

Because his sometimes-obfuscating style, often employing ill-considered or formulaic phrasing, creates ambiguity, his focus is not always clear. For example: “These men found that a new, alternative consensus to the one that shattered in the 1960s proved elusive.” It is unclear whether these men sought such a consensus or whether that search is merely the author’s construct. Nor is it clear whether members of the class of ‘64 helped cause events or were simply affected by the effects of events, or both simultaneously. But the material is so rich that I believe readers who make the effort to sort it all out will find the effort worthwhile.

Reaching back to the decades before the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, one revealing context for reading this book is John G. Waugh’s analysis of The Class of 1848: From West Point to Appomattox: Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan and Their Brothers (1994). Reaching forward over the decades to the present, another revealing context for reading this book is the recently erupted and on-going perspectives on free speech around the racism controversies at Yale, Princeton, Harvard, Amherst, Missouri, University of Tennessee, Louisiana State University, and Pomona, among others. As for Yale itself, who better to turn to for a perspective, however imbued with new conservative bias, than William F. Buckley, Jr. and his 1951 book God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom.”

No use turning to me because when I was a graduate student in the Yale School of Drama in 1959-1960, fear of nuclear winter seemed to make everyone so politically tongue-tied that Ayn Rand’s visit to Yale could elicit only mild liberal statements and questions—which she readily squelched.

In the tradition of Yale’s dedication to service to the community, David Madden is an active member of the Western North Carolina Yale Alumni Organization in Asheville. The author of over 50 books of fiction and nonfiction, he is at work on My Intellectual Life in the Army.