By Colin Rafferty

The political reactions to First Lady Michelle Obama’s anti-childhood obesity initiative or the Reagan-era USDA ketchup-as-vegetable controversy remind us that food has often been a politicized element of the American landscape. Debates over who should eat and drink what, when, where, and how (a recent Onion headline: “Woman A Leading Authority On What Shouldn’t Be In Poor People’s Grocery Carts”) have been commonplace in a country founded, in part, over objections to the taxation of tea and sugar.

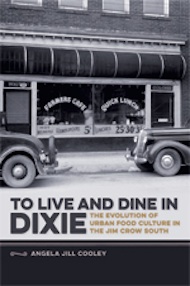

Angela Jill Cooley focuses her engaging book on a specific time and place in the United States—the Jim Crow era of the American South, spanning from the late 19th century end of Reconstruction to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 70s. In six self-contained chapters as well as an introduction and conclusion, she analyzes various case studies of how ideas of whiteness and blackness were established and enforced through varying venues of food—everything from restaurants, to cookbooks, to home economics programs.

Appropriately for an author trained in both cultural history and law, Cooley brings a remarkable cultural analysis of each case to her project, part of Georgia’s Southern Foodways Alliance Studies in Culture, People, and Place Series. An early chapter considers new technologies, including electric stoves and instant foods, and the pressures they placed on white Southerners looking to maintain an “authentic” (the term is always suspect in Cooley’s book, as its original usage suggests a nostalgia for an antebellum existence that never really existed) style of southern cooking (and by extension, living). If African American servants (originally slaves) were the source of this revered cooking and its accompanying knowledge, then how could a Jim Crow-era family correctly enforce a kind of kitchen segregation? Often, Cooley argues, it was done through a careful regulation of the kitchen as a racially encoded space, fraught with complications. “For a generation of newly urban and consumer-oriented southern women,” she writes, “the notion that ‘unclean’ black women cooked meals in ‘clean’ white kitchens seemed inconsistent with the idea of racial purity.” However, other whites argued that lower-class women should not work as servants, because to do so would associate the white woman with labor and not an elevated, superior status.

Cooley soon moves from the kitchen to the restaurant, where a more public performance of eating takes place. She explains the evolution of the café in the south, from their initial emergence as places of low morality (including prostitution) to places where whiteness and its supposed moral superiority could be defended; Cooley’s final chapter covers Georgian Lester Maddox’s battles with protesters over his restaurant, which provided not only a narrative to accompany the signing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 but also provided the segregationist restaurant owner with a platform to run successfully for governor two years later. These public spaces provided a front-page venue for protesters on both sides of the Civil Rights to negotiate (often with violence on the part of the segregationists) the idea of citizenship.

Cooley’s approach results in a fascinating exploration of the questions that food in the Jim Crow south raised, and how varying groups responded to it. Her style is decidedly academic, and readers from the general public may be daunted by her analytical voice. However, those who persevere will find a richly detailed book that will make them consider what the acts of preparing and eating mean to them as cultural participants—those given to puns might even say that Cooley has provided her readers with ample food for thought.

Colin Rafferty (ΦBK, Kansas State University, 1998) teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Mary Washington is home to the Kappa of Virginia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.