By Katy Sternberger

Writing and gardening often go hand in hand. All across England, authors created special places where they could take solace, stimulate their creativity, and write. The Writer’s Garden: How Gardens Inspired our Best-loved Authors by British garden writer Jackie Bennett is a perfect blend of biography, history, and garden design.

Arranged by writer, the book offers a great variety of poets, novelists, biographers, and children’s authors, including Jane Austen, Robert Burns, Agatha Christie, Winston Churchill, Roald Dahl, Beatrix Potter, Virginia Woolf, and William Wordsworth. Twenty writers are featured in all. The gardens are just as varied, from cottage gardens to formal estate gardens. Bennett tells the writers’ biographies through the gardens they created and managed. Her writing is succinct, and the accompanying photographs of the English countryside are stunning.

Each chapter ends with a brief description of the current state of the garden and a timeline describing when and in which gardens the authors wrote their greatest works. In addition, Bennett makes “Literary Connections” throughout the book, noting how other writers have benefited from the gardens. “Garden Visiting Information” at the end of the book enables readers to plan a tour of England to see the homes and gardens that heavily influenced the writings and lifestyles of these important authors.

Many English writers, such as Jane Austen, who grew up during the eighteenth century surrounded by farmland, learned how to tend plants and animals and developed an interest in gardening that would later permeate their work. Gardens were not only a quiet retreat designed to provide inspiration and a way to cope with tragedies, but the writers were actively involved in creating and maintaining their gardens. For instance, Beatrix Potter, who was possibly influenced by the designs of Gertrude Jekyll, and Roald Dahl, who started a collection of orchids, were knowledgeable about the different kinds of plants they used.

Some gardens have remained well taken care of over the years and look much the same as they did when they were created—which is a hard thing to do since gardens are “living places” and require constant maintenance. Some gardens are now privately owned or have been transformed for other purposes, such as Charles Dickens’s home, Gad’s Hill, which became a school. Some gardens no longer exist at all. As Bennett says, it is mostly by luck that we still have so many writers’ gardens, but caretakers are realizing the value of the timeworn ones and are striving to revive them.

John Ruskin is considered an early environmentalist; he used native plantings at his country house, called Brantwood, and tried to leave the landscape wild in the style of garden designer William Robinson. Bennett explains that Ruskin “was the first to suggest that we should ‘conserve’ buildings—not restore them. He pointed out that buildings belonged to the people who built them and to the people who would come after them—the current generation were simply custodians and should not do anything to the buildings the could not be reversed.” This statement seems to summarize the subtle message of the book: that writers’ gardens have a lot to say about the people who planted them and how gardening principles have evolved over time—and this is history well worth preserving.

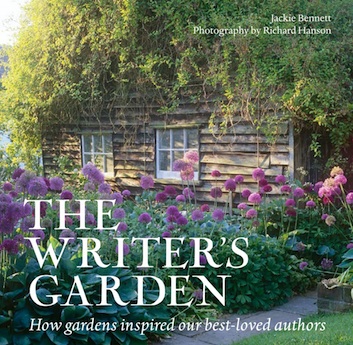

Photo at top: Thomas Hardy’s cottage.

Katy Sternberger (ΦBK, University of New Hampshire, 2012) is a writer, editor, and researcher. After graduating from the English/journalism program at the University of New Hampshire, she is now pursuing her master’s degree in archives management at Simmons College.