By Jay M. Pasachoff

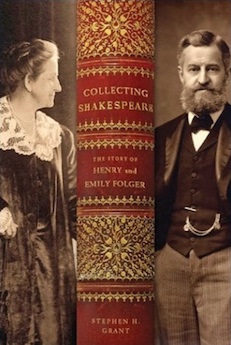

The tale told by Stephen Grant covers not the literary content of Shakespeare’s plays but the physical books, especially the First Folio, the 36 plays published together for the first time in 1623. The story is one that will be appreciated by people who have collections of any kind—whether it is doll’s houses, stuffed animals, or books.

On November 23, 2014, the discovery of a First Folio at a small library in northern France made the front page of The New York Times, which reported that it brought “the world’s known total of surviving first folios to 233.” “This is huge,” said the expert quoted. Astoundingly, 82 of the total, or 35 per cent, were collected by the Folgers, and are now in one place: the Folger Shakespeare Library on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. An auction a half dozen years ago brought the sale of one for over $5 million. Surely the security against theft and fire must be extreme, but it still seems to me too dangerous to have so many copies in one place.

Visitors to the Folger Library don’t get to see them all, but they do get to see a changing display of interesting exhibits usually related to the 17th century or other long-ago periods. The Library as has a theater, with performances of Shakespeare or other period plays and concerts.

Henry Folger was, a hundred years ago, an Amherst College student and roommate of the son of a close associate of John D. Rockefeller, and both new college graduates were given jobs in the organization. Folger was what we would now call a quant, and his statistical and organizational abilities eventually made him president of Standard Oil of New York, so the book being reviewed even goes into discussion of Ida Tarbell and the muckrakers. Folger spent his huge salary and more, apparently from an investment, on books—especially First Folios. The book even has a photo of a $100,000 check that went toward the purchase of books, though not entirely at the time for a single First Folio, so Folger’s denial to Rockefeller on the golf course that he had not paid $100,000 for a book was barely true. Anyway, Folger goes down as someone as fortunate in his choice of college roommate as Chris Hughes, whose Harvard roommate was Mark Zuckerberg and who is now spending some of his Facebook-founding fortune on remaking The New Republic. Folger later wrote to the president of Amherst College that “My own interest in Shakespeare started from writing for a Shakespeare prize, offered at Amherst for only a year or two, which, by the way, I failed to get.”

The Harvard-Smithsonian astronomer and historian-of-science Owen Gingerich, the world’s expert on Copernicus, has found about three hundred first editions of Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus from 1543 and about as many second editions. But Gingerich is a scholar, and he has analyzed Copernicus’s thought processes and the content of the book in the context of the times and of the history of astronomy. Henry and Emily Folger, by contrast, seem to have been collecting for the sake of collecting.

Henry did arrange to have the copies compared with a Hinman Comparator, though, a device similar to the blink-comparator used by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930 to discover Pluto (now upgraded to be the brightest of a class of tens of thousands of Kuiper belt objects instead of a trivial member of a class of “planets,” containing only 1/5 of 1 per cent of the mass of Earth). I’ve seen the Hinman Comparator on display in the Folger’s beautiful display room.

Folger claimed not to want duplicates, and he found differences among the copies, whether it was the association with past owners, the minuscule thickness of the paper, or chunks of type as set by different typesetters. The Library long claimed to have 79 First Folios, but in 2011 that number was changed to 82, not because any new ones had been purchased but because of a change in the way that incomplete copies are counted. The Library has about 10,000 Shakespeare editions in all.

An interesting chapter in Grant’s book describes the rivalry and parallelisms between the book-collecting of Folger and Henry Huntington, whose Library and Museum in San Marino, California, opened a few years before the Folger first received general readers in January 1933. (I have just checked, and find that the Huntington Library and Museum has four First Folios.) A surprise for me in a subsequent chapter was the description of how the Folger Shakespeare Library is actually owned by Amherst College, according to Henry Folger’s will, and also support from his widow, Emily. Only in 2005 did the direct administration of the Folger change from the Amherst trustees to a “quasi-autonomous Folger Library Board of Governors to replace the Amherst trustees’ committee,” with Karen Hastie Williams, from the Amherst board, as the first chair.

The Folger Library has announced that a few of its copies of the First Folio will circulate in 2016 on four-week loans to venues in each of the 50 states + DC + Virgin Islands + Puerto Rico. The year will mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Our Chapin Library of Rare Books at Williams College has a First Folio, a Second Folio, two Third Folio variants, and a Fourth Folio, and I had the pleasure of showing the set of all four folios to a seminar of students this spring along with reading about Shakespeare’s allusions to astronomical topics and a visit from one of the Folger’s former directors, Werner Gundersheimer, who lives in Williamstown, to learn about Shakespeare’s 17th-century milieu.

Astronomer and author Jay Pasachoff is the director of Hopkins Observatory and Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College.