By Fred H. Lawson

What the Founding Fathers actually thought about Islam is of more than antiquarian interest. Various movements that exercise political influence in the United States today claim that their platforms enshrine the principles and practices of the statespeople who initially established the Republic. And perhaps the most widely held belief among proponents of the so-called “original intent” of the Founders is the notion that America from the outset has been a Christian nation, albeit one that tolerates all faiths.

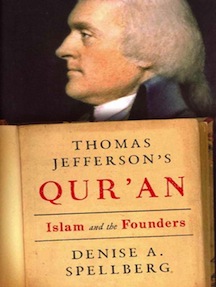

It may therefore come as a surprise for many readers to learn that Thomas Jefferson had enough interest in Islam to own at least one copy of the religion’s sacred book, the Qur’an, and even more shocking to hear that he was a firm supporter of “the rights of Muslims” as full citizens of the new polity. These things were not news to his political opponents, who on a number of occasions charged that he was an “infidel” whose leniency toward non-Christians threatened to drag the new country back into tyranny. In fact, “Muslims” for most early Americans were synonymous with “Turks,” so the politics of Islam were indistinguishable from forms of governance associated with the Ottoman Empire or, even more pertinently, the undisciplined Turkish rulers of North Africa.

But did the Qur’an or any other aspect of Islam have an impact on Jefferson’s thinking and actions? Apparently not. Denise Spellberg speculates for several pages about what Jefferson “may have learned” from the lengthy introduction to the edition of the sacred text that he owned, only to conclude that there is “virtually no evidence” that he “gleaned anything from [George] Sale’s work to enhance his own knowledge and judgment” about political or religious matters. By the same token, Jefferson’s dealings with the unruly governors of Algiers and Tripoli showed no trace of religious motivation, in sharp contradistinction to the expressed sentiments of his bitter rivals John Adams and John Quincy Adams.

In fact, the book turns out to focus on other things besides Jefferson’s understanding of Islam. The first quarter of the text surveys a broad range of European writings about Muslims, some sympathetic but most highly antagonistic toward Europe’s long-standing religious adversaries. Another lengthy chapter offers an enlightening overview of debates surrounding the ratification of the U.S. Constitution that made direct or indirect reference to Islam, while a somewhat shorter chapter lays out the radically democratic ideas of John Leland, a Baptist minister who championed the civil rights of all American citizens, explicitly including Muslims.

Spellberg concludes with a rather belabored polemic about religion and politics in the contemporary United States. Things have gotten bleaker for American Muslims since September 2001; Representative Keith Ellison of Minnesota caused a stir by taking the oath of office using a Qur’an; President Barack Obama has been alleged to be a Muslim; Christian extremists have been railing against Islamic law (shari’ah) and the construction of mosques in prominent locations. “And so the ultimate strength of those guarantees that in the eighteenth century deliberately included Muslims are now being tested, together with the seriousness of our national commitment to the cherished ideals of religious freedom, political equality, and pluralism.” Thomas Jefferson’s nuanced, conflicted relationship with Islam merits wider public acknowledgement, further scholarly exploration and a well-reasoned and clearly articulated set of implications for the twenty-first century.

Fred H. Lawson (ΦBK, Indiana University, 1973) is the Lynn T. White, Jr. Professor of Government at Mills College and a resident member of the Zeta of California chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.