By Carol A. Leibiger

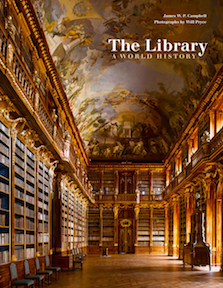

James Campbell, Director of Studies in Architecture and History of Art at Queen’s College, Cambridge, and Will Pryce, a photographer with training in architecture, have produced an informative and sumptuously illustrated history of library buildings. Viewing libraries as the edifices that house book collections (whether in the form of tablets, scrolls, or codices), Campbell traces the history of library structures that hold and keep books undamaged and secure, provide access to books, and offer comfortable and attractive spaces for readers to utilize books. The author touts this work as the first to tell the story of library architecture around the world and through time, examining eighty-one libraries in twenty-one countries in their various forms and functions (academic, private, and public libraries, as well as archives).

Arranged “broadly chronologically,” The Library traces the ways in which developments in the form and production of books have influenced library structure, climate, fittings, security measures, decoration, and iconography. Beyond their function as repositories of books, libraries are presented as expressions of their cultural and intellectual contexts and understandings of knowledge and its place within each time period examined. Libraries combine both beauty and utility in their conception, i.e., “libraries…are designed to be seen.” Finally, Campbell traces the effects of specific groups (readers, patrons, architects/designers, and librarians) on library design, in both structure and decoration, over time. He has provided a detailed and fascinating look at the development of library buildings and the notion of the library as “an extraordinary variety of spaces in which to read, to think, to dream and to celebrate knowledge.” The work goes beyond communicating the history of libraries, however, as it also corrects misapprehensions about them. For example, Campbell emphasizes the importance of ancient libraries in Middle East as the origin both of types of libraries that exist today and the idea of the “beautiful library.” He also revises the misconception that printing originated in the West, indicating that Asians actually developed the process more than 700 years earlier than Europeans. Such information represents important correctives to Western (mis)understandings of books and libraries.

Despite the mention of non-European cultures, however, The Library’s focus is not global. While it begins with the earliest, Middle Eastern, archives and ends with the role of Chinese libraries in advancing literacy, the focus is on Western—more specifically, European—libraries. The author makes forays into Asia and North America, but he leaves Africa (except for the library of Alexandria), South America, and Oceania out of the discussion. A work that seeks to encompass the libraries of the world across time inevitably involves choices. However, the author does not stipulate his criteria for inclusion, nor does he justify the overwhelming preponderance of Western libraries, Western architecture and design, and Western historical and cultural periodization in this book, whose subtitle promises a global history.

A library is no more only a place that houses books than it is merely a collection of services related to books and information. This work honors the notion of “library as place” and salutes the architects, designers, and patrons who provide beautiful and useful spaces for readers. However, Campbell ignores, except to belittle, other potential collaborators in library design, i.e., the librarians who provide services essential to accessing information sources like books by readers. The author considers librarians unimaginative (accusing them of arranging “dull, rectangular libraries with regularly spaced desks…full of bored-looking people”) and, worse, obsolete (praising library design that makes “librarian surveillance of readers” unnecessary and moves librarians to “reception areas outside the library itself where they can more readily [perform] duties without disturbing the readers”).

The Library is a fascinating look into the history of library buildings across time and space. With its large format and stunning photographs, the book is both decorative and educational, like the libraries it describes. However, it is not the last word, either on libraries or library buildings. Those interested in supplementing this treatment of library edifices would be well served by Patrick M. Valentine’s A Social History of Books and Libraries from Cuneiform to Bytes, which treats the social and cultural history of libraries, regardless of the structures that house them.

Carol A. Leibiger (ΦΒΚ, University of Connecticut, 1977) is Associate Professor in the University Libraries at the University of South Dakota and a resident member of the Alpha of South Dakota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.