By Louis J. Kern

At the outset, Gravett observes that “the official history of comics is a history of frutstration; . . . [it is] a medium locked into a ghetto and ignored by countless people.” This multi-faceted work makes a powerful case for recognizing the legitimacy of the vernacular hybrid medium of comics—from newspaper comics and comic books to graphic novels, digital, interactive comics, and hyper-comics—as a popular art form. It provides something of a guide to reading comics and decoding their visual texts, an elliptic version of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1993).

Though the genre developed incrementally over centuries, Gravett is concerned only with a history of comics in newspapers and comic books divided into discrete narrative panels. He accepts the appearance of Richard Fenton Outcault’s Yellow Kid in the New York Journal (October 25, 1896), that included the first use of speech balloons, as the definitive birth of comics. But this rationale is weak since political cartoons had featured speech balloons since the eighteenth century. Remarkably, Gravett does not consider the origins of the comic book. There is no mention here of Rudolphe Töpffer’s The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck, widely recognized as the first comic book, published as a freestanding supplement to Brother Jonathan (New York, 1842).

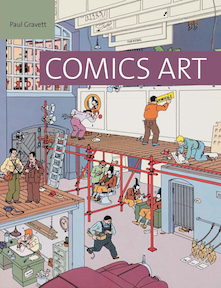

This lavishly illustrated volume is international in scope and comics aficionados may appreciate the opportunity to encounter other national traditions like France’s extensive bandes dessinées as well as individual artists like Egypt’s Magdy El Shafee and France’s “Moebius” (Jean Giraud). Gravett is at pains as well to demonstrate the role of comics as agitprop against racism and to “express real psychological anguish.” Most affectively he discusses Keiji Nakazawa’s powerful ten-volume series on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Barefoot Gen (1972-2010)—made into animated films in 1983 and 1986—and white South African cartoonist Anton Kannemeyer’s “Pappa and the Black Hands” (2009), that confronts censorship of cartoons, since it is an explicit response to Belgian cartoonist Hergé’s (Georges Prosper Remi) Tintin in the Congo (1946), that embodied such controversially offensive racial stereotypes that it remains unpublished in the U.S.

A primary strength of the volume is its attention to the inter-disciplinary nature of the visual arts. Gravett points out that Picasso drew a six-panel travelogue (1904) and commented that “the only thing I regret in my life is not having made comics.” But the art form that most closely resembles comics is film. The two media have been interactive. Jack Kirby acknowledged his debt to cinema, and a whole generation of cartoonists learned to think visually and sequentially and to conceptualize comics as producing movies on paper from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941). In films, elaborate storyboards resemble comic books. Physically and functionally, both arts consist of separate images—individual photographs on a film strip and individual panels on a comic page—separated by blank space. For both, the continuity of the image and the action takes place in the blank liminal space where the unconscious and subconscious mind connects the discreet photographic or graphic images. Both rely on the retention of images by the eye to give the illusion of uninterrupted fluidity and narrative unity. These characteristics make these visual arts more susceptible to interactivity, a trend clearly observable in hyper-comics that increasingly incorporate virtual reality and user-generated plot development.

Gavrett here redeems an oft-contemned medium in a broad survey of comic art and its history and functions in a book that will be read with interest by both comics fans and occasional readers of graphic novels.

Louis J. Kern (ΦBK, Clark University, 1965) is professor emeritus of history at Hofstra University. Hofstra University is home to the Omega of New York Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.