By David Madden

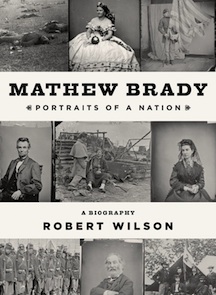

Readers of Robert Wilson’s Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation are well-advised to set aside any disappointment at discovering that not enough information exists to construct a comprehensive biography, because on the general subject of photography during the Civil War his book is superb.

Among those who are fairly well aware of the history of the Civil War, the name Mathew Brady is one of the best-known. Less-known is the fact that Brady himself took relatively few of the Civil War photographs on which his fame rests today. But he did indeed take photographs of Lincoln, seated in “Brady’s chair.” “Brady and the Cooper Union,” said Lincoln, “made me president.”

Wilson, editor of The American Scholar and author of two other books, makes an excellent case for our settling for Brady as “historian,” based mostly on his national vision of the role of photography and his extraordinary acumen as a consummate self-promoting, innovative businessman. Wilson also supports the claim Brady relentlessly made for photography as an art form.

Who, if not Brady, did take the photographs that made the American Civil War the most comprehensively photographed war until perhaps World War I? Two of the finest photographers were trained in Brady’s celebrated New York and Washington DC studios—Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan. When Brady is not the hard focus, Wilson adroitly conjures up his hovering presence by detailing the activities of those and other Brady photographers at battle sites.

Two of the finest of all photographs of General Grant and of General Lee are mostly likely Brady’s own—Grant in uniform leaning “casually” against a small pine tree, hand on hip; Lee behind his house in Richmond the day after Lincoln’s assassination.

While perhaps feeling somewhat impatient when Brady is absent for a number of pages, readers will likely be impressed by Wilson’s ability to narrate battles. Waffling on a grand scale is acceptable if the overall effect is indeed grand, as it is with this first full-length biography.

Brady rather often moved his studios and added new ones, following the inventions of new camera equipment and innovative procedures, sometimes partnering with other studio owners and drawing upon their photographers. Having come from the Irish lower class, he aspired to wealth and respectability. He responded to and himself created the allure of celebrity, proudly exhibiting portraits of presidents, generals, and other luminaries in his palatial National Photographic Art Gallery. But not until 1880 would the public see the Civil War photographs in magazines, having seen only copies in woodcuts and engravings.

After the war, his health and fortunes gradually declined, and his wife died. Shortly before he died, an impoverished national treasure, he had prepared a lantern slide lecture to show what he called his Civil War photographs in Carnegie Hall, still making a claim for which Wilson argues concurrence: “without the power of his name to give value even to those he did not take, the vast collection of images that remains [over 10,000] … would not exist today.”

Because so many details of his life are unrecorded, Mathew Brady remains a mystery. Amidst the contextual conjectures that paucity of facts demand, Wilson frequently strives to ascertain differences between myth and fact, as when we were told that Brady had himself photographed at the field where General Reynolds was killed—the wrong field, we now know. But one cannot ignore the fact that long-known myths are more powerful, effective, and lasting than discovered facts that debunk myths.

Author of several books on the Civil War, including Sharpshooter, a novel, David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979) is founding director of the U. S. Civil War Center.