By Serena Broome

Former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young once stated, “If it hadn’t been for Benjamin Mays, there probably wouldn’t have been a Martin Luther King.”

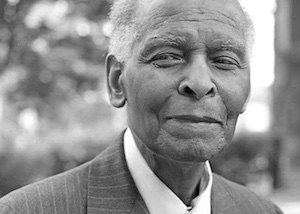

Benjamin Elijah Mays (ΦBK, Bates College) is remembered for the mentorship he provided to younger advocates during the Civil Rights movement—he is known as the movements’ intellectual conscience. He was deeply respected as an educator, minister, and presidential advisor. As we note the 41st year since his passing on March 28, 1984, we reflect on his legacy—the gleam of light in his eyes is a silent, good-willed plea for us to strive towards higher ideals—as he did throughout his life.

Mays was born in 1894 in Epworth, South Carolina, and was the youngest of eight children. In his memoir, Born to Rebel, he remembered, “Somehow, I yearned for an education. Many a day I hitched my mule to a tree and went deep into the woods to pray, asking God to make it possible for me to get an education”. Despite the hardships of the post-Reconstruction era, he graduated first in his class, completing the course requirements in three years. He proceeded to receive a B.A. from Bates College, and his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Although Mays had excelled at mathematics and philosophy, he decided to major in theology, which benefited from his gifts as an orator. He conducted the first sociological study on African-American churches, seeking to embolden his community from the pulpit.

In 1940, Mays was elected President of Morehouse College, which had a humble beginning in a church basement in 1867. Recognizing the profound impact that a liberal arts education had on his life, Mays made painstaking efforts to increase the school’s endowment and improve the quality of education for its students. His influence at Morehouse was especially remembered by the spirit he instilled in his students during his weekly sermons at the Morehouse College chapel. During his sermons, he introduced the principle of nonviolence.

When Mays began an early admissions program at Morehouse in 1944, he met a 14-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., and a lifelong mentorship began. As King began to gain national prominence as a leader in the Civil Rights movement, Mays provided unwavering support. In particular, during the Montgomery Bus boycotts, Mays encouraged King even when his own father was opposed. For his guidance, King would call Mays his “spiritual mentor” and “intellectual father.” At the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, Mays delivered the benediction. At King’s funeral in 1968, Mays eulogized him, fulfilling a promise they made to each other.

In 1968, Mays oversaw the installation of a Phi Beta Kappa chapter at Morehouse College, which had been a dream of his. Through his efforts, Morehouse became one of the leading liberal arts schools in the country. After retiring from Morehouse, Mays continued to serve his community. He was elected as the first African-American President of the Atlanta School Board of Education, where he led desegregation efforts. Morehouse college alumnus, Samuel DuBois Cook, eulogized his noble character, “Dr. Mays used to tell us, you’ll die unheralded, unrecognized, but never sell your soul to anybody, to anything. You have to stand by your beliefs, stand by your selfhood, stand by your ideals, though the heavens fall.”

Leaving behind a rich legacy, Mays remains a powerful example of tenacity, a beacon of hope. He mentored his students through his firm resolve and piercing insight, forming the intellectual foundations of a movement that empowered others to assert their dignity and humanity.

Serena Broome graduated early from UC Davis majoring in political science. She inducted into Phi Beta Kappa during her junior year. UC Davis is home to the Kappa of California chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.

Photo at top courtesy of Morehouse College.