By Isaac Hughes

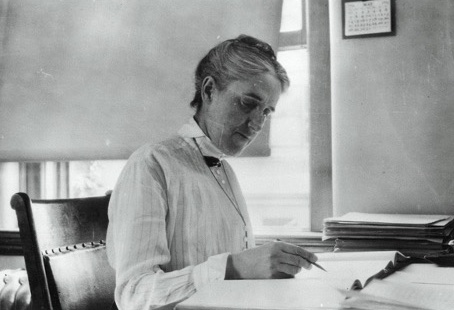

This December marked the 100-year anniversary of the death of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, a member of Phi Beta Kappa and an astronomer whose legacy and groundbreaking findings remain largely obscured by history.

Leavitt graduated from Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1888 at the age of 20. At Radcliffe she developed her passion to better understand the stars above, and after completing her degree, she worked at the Harvard College Observatory as a “computer”—a tedious, demeaning role often reserved for women at the observatory.

Often described as soft-spoken, Leavitt quietly but diligently continued to put her curiosities to work and make her own astronomical observations despite the limiting nature of her job. These observations led to her most critical finding—a direct relationship between the brightness of certain stars (known as pulsating Cepheid variable stars) and their distance from Earth.

This relationship (sometimes referred to as the period-luminosity relation), allowed astronomers to measure the magnitude of the universe much more completely than ever before. In short, Leavitt’s discovery allowed astronomers to finally measure the size and scope of outer space.

Even though Leavitt’s work fundamentally changed how astronomers look at the world, she died in 1921 without ever receiving adequate credit for this discovery. Instead, it was her male bosses, Edward Pickering and Harlow Shapley, who ended up piggybacking on her work and receiving the bulk of the credit.

George Johnson, author of Miss Leavitt’s Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe (W.W. Norton, 2005), argues that now more than ever we must shine a light on the life of Henrietta Swan Leavitt.

According to Johnson, Leavitt has been treated as “a footnote in the history of how we learned measure the universe.” Shifting the narrative to make this footnote the centerpiece is a task that Johnson urges astronomers, historians, and citizens alike to undertake.

How do we go about remembering Henrietta Swan Leavitt? Johnson suggests simple yet powerful changes in the way we talk about her findings.

“I think the most important thing is probably more widespread use of the term ‘Leavitt’s Law’ to describe this discovery instead of referring to it abstractly as though it just fell from the sky and we’ve known it all along,” Johnson said.

By giving more explicit credit to Leavitt and championing her story, Johnson is hopeful that the next 100 years will bring true recognition of her work and its significance to the field of astronomy, and serve as a reminder and motivation for others to pursue their intellectual passions, regardless of the hurdles they might face.

For Johnson, Leavitt’s life is “a reminder that anyone out there might come into the world with a combination of curiosity and various other skills that will come unexpectedly to make some important discovery that is later built upon by generations of scientists after, and gets embedded in the great tissue of knowledge.”

As we pass a century since the life of Henrietta Swan Leavitt, perhaps it is time to look up into the night skies and consider the countless other unacknowledged stars whose scientific discoveries have been unduly shrouded.

Isaac Hughes is a recent graduate of Knox College, where he majored in environmental studies and philosophy. He was inducted to Phi Beta Kappa as a junior in 2020.