By Krista Shaw

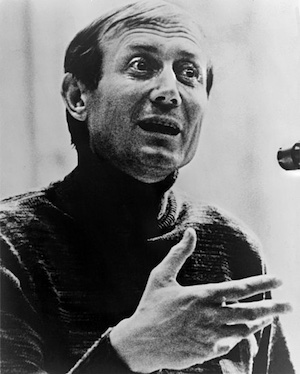

Yevgeny Yevtushenko is best known for his poetry, specifically for those poems in which he boldly criticizes the policies of the former Soviet Union and the governance of Joseph Stalin. Yevtushenko’s best known poem, “Babi Yar” was among the first publications to confront and decry the anti-Semitism plaguing Soviet Russia.

Born on July 18, 1933, Yevtushenko lived through Stalin’s Great Purge, during which both of his grandfathers were arrested under charges of being state enemies. Yevtushenko was raised in the remote Siberian town Zima Junction, far from the fighting of the Second World War; yet, the war’s effects on him and on Russia became influential in his later poetry. After the war Yevtushenko briefly attended the Gorky Institute of World Literature in Moscow, but he dropped out in order to pursue writing. In 1952 Yevtushenko published his first collection of poetry and became a member of the Soviet Writers’ Union, but as he began to write increasingly dissident poetry, he was expelled from the group.

When Khrushchev came to power and temporarily offered increased artistic freedom and openness to the West, Yevtushenko traveled Europe and wrote progressively more forceful poetry. Named for a ravine outside Kiev where Nazi occupiers massacred tens of thousands of Jewish people during World War II, “Babi Yar” was published in 1961 to both Soviet and World acclaim. The poem’s words still carry a daily message to the world. A passage from it is inscribed on a wall of the United States Holocaust Museum, serving as a constant witness to the brutality suffered by the Jewish people during World War II. Because of his brave support of human rights and his inclusion of that message in lyrical poetry, Yevtushenko has been nominated for the Nobel Prize multiple times.

Yevtushenko poetry makes a resolute political stand, but the poet’s overarching message is much larger than a mere criticism of policy. In a recent poetry reading at the University of Dallas, Yevtushenko called for men to “find a common language.” He spoke of his sense of the kinship of humanity. “I have Latin blood, I have Swedish blood, Ukrainian,” Yevtushenko said. “Even I count Georgian blood – there was one time that I had food poisoning in Georgia. One Georgian, the wife of a taxi-man, she had the same group of blood, and she gave me a liter and a half — all of us, we are long distance relatives.”

Yevtushenko’s desire to establish relationships with others is apparent in the way that he engages his listeners and includes them in his poetry. When Yevtushenko read at the University of Dallas, he asked his audience to sing along to the chorus of the Beetles’ “Yellow Submarine.” In the midst of his impassioned reading, he would stop to signal the audience’s queue to sing with him.

Yevtushenko also asked students to read his poetry along with him so that the audience could first hear the expression and feeling of the poems as he read them in their original Russian form and afterword hear the English translations of the poem in order to understand their full message. In certain poems Yevtushenko read one role and allowed students to take on the others so that his poem was acted out as a drama. Yevtushenko’s sincere belief in the power of poetry shone through when, upon hearing a student’s performance of a part of “’Yes’ and ‘No,’” he spontaneously took her hand and gallantly kissed it.

Reaching out to his audience through his vigorous and emotional performance, Yevtushenko created a taste of the unity he wishes to see amongst all people, the unity which he lovingly called “the dream of our birth, the dream of centuries.”

Yevtushenko is an honorary Phi Beta Kappa member and a professor at the University of Tulsa. He spends half of each year teaching classes in Russian literature and cinema and the other half traveling throughout the United States and Russia.

Krista Shaw is a senior at the University of Dallas majoring in English. The University of Dallas is home to the Eta of Texas Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.