By Allen D. Boyer

Winner of ΦBK’s 2024 Christian Gauss Award

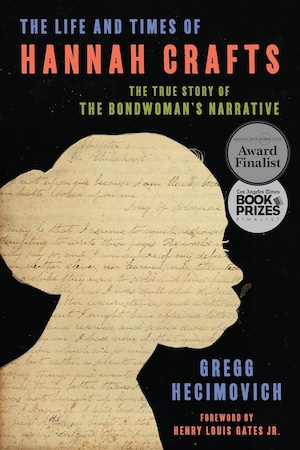

In The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of The Bondwoman’s Narrative, Gregg Hecimovich has overcome a daunting series of challenges. He has learned the identity of a long-dead novelist who was born with no surname and later employed a series of surnames; who disguised herself to escape slavery, and carefully covered her tracks; who absorbed literature that she was never meant to read and penned a novel so accomplished that some doubted that she could have written it; whose only known work survived in a single manuscript, without date, location, or provenance; and whose fiction was closely autobiographical—except when it was not.

In 2001, Henry Louis Gates bought at auction a manuscript, neatly penned and stitched together. On its first leaf, it was titled The Bondwoman’s Narrative, by Hannah Crafts, A Fugitive Slave Recently Escaped From North Carolina. It contained a vigorous tale of enslavement and escape, sometimes cold-eyed, sometimes sentimental, written by an author familiar with (among others) Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens, Jane Eyre, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nothing more was then known of The Narrative or its author, save that the manuscript was possibly the earliest novel written by an African-American woman and the only known novel written by an American fugitive slave.

Gates, who supplies the foreword to this book, broke the first ground in establishing the history of the Narrative. Twenty years’ research has brought much more to light. Of the many scholars involved, whose work he freely acknowledges—genealogists, historians, forensic experts, students of Victorian literature—Hecimovich has proved the most dogged.

Hannah, the protagonist of The Bondwoman’s Narrative, is a house-slave for a family named Wheeler. This provided a vital clue to the author’s identity; here could be recognized John Hill Wheeler of North Carolina, a politician and planter, someone whose career could be tracked and whose family papers identified his slaves. Researchers were then confounded by a slavery-era marital-property dispute. Although Hannah worked for the Wheelers, she technically remained the chattel property of their in-laws, the family of Lewis Bond. As Hecimovich writes, because Hannah counted as a member of the Bond household—by ownership and, as well, by blood—this means that The Bondwoman’s Narrative is actually a sardonic punning punchline of a title.

Crucially, Hecimovich has clarified the North Carolina plantation where Hannah served and from which she escaped. The Narrative mentions rice, lemons, and oranges. Those would not grow, he observes, near the Wheelers’ plantation of Ellangowan, north of Charlotte in the chilly Piedmont. They fit the climate of Liberty Hill, another Wheeler plantation, outside low-lying Murfreesboro. And in Murfreesboro, significantly, young ladies attending the Chowan Baptist Female Institute, “reciting Dickens’s Bleak House and Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” boarded with the Wheelers. The schoolgirls’ books and practice essays would shape The Narrative.

The daughter and granddaughter of slave owners, Hannah was no more than a quarter black. As an author, she skewered the self-deceiving pride that some mixed-blood women took in their white relatives’ prominence. She could see first-hand that such connections might mean nothing (or, sometimes, everything). One of Hannah’s Wheeler cousins may have taken a slave master’s sexual advantage of her; another white Wheeler relative apparently bought the man’s suit in which Hannah disguised herself to make her escape.

Hannah Bond fled to freedom in May 1857. Her first destination was probably Washington and the First Colored Baptist Church, a mainline station on the Underground Railroad. By August she had reached central New York, the Cortland County hamlet that survives as McGraw, outside the county seat of Cortland. There New York Central College, a struggling Free Baptist school, served as an abolitionist outpost. When rumors arrived of slave hunters, Hannah moved outside town, to the Quaker farmhouse of Horace and Harriet Craft.

On the Craft farm, Hannah resumed writing a book she had started earlier, on the Wheeler family’s watermarked stationery—and which, incredibly, she had carried north with her. Originally, she had written her owners’ surname as Wh___r; now she began spelling it out. She renounced the name Hannah Bond and took (Hecimovich writes) a nom de guerre, borrowed from the husband and wife who were sheltering her. “Now safe from her captors, the author identified the Wheelers in her novel, returning to the manuscript to fill in their surname. With these changes, Crafts realized and declared her liberty, defying at once the will of her pursuers and the laws of a country that defined her as property.”

For her fictional self, Hannah Crafts imagined a reunion with her mother, who in life had been sent to distant Tennessee when she herself was very young. She invented a mixed-blood mistress to run away with her fictional double, only to be stalked by a Southern lawyer of Dickensian malice and cunning—perhaps to lend her story gothic dimensions, perhaps to express her own fears in the safe distance of fiction. She gave The Narrative symbolic overtones: she imagined being saved from drowning by the same angelic Quaker matron who had taught her to read.

By 1860, Hannah had married Thomas Vincent, a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and adopted yet another surname. They survived together well into the new century. Census records and church histories show them settled in Burlington, New Jersey, across the river from Philadelphia, with Hannah Vincent remembered in the Bethlehem AME Church, a tireless teacher, steward, and treasurer.

Write like a god, live like a bourgeois, Flaubert said. Did the author of The Narrative finally take that path? Apparently, Hannah Bond’s flight to freedom and Hannah Crafts’ literary endeavor became crossed-out early chapters of Hannah Vincent’s long, quiet family life. The high-pitched drama of The Narrative lacks a known sequel. But did Hannah write nothing more? For a century, few suspected that the author of Little Women had begun her career with tabloid magazine “blood and thunder tales” of madness, passion, and revenge. Further investigation of Hannah’s life may say more about her career.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) grew up in Mississippi. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.