By Allen D. Boyer

Shortlisted for ΦBK’s 2024 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

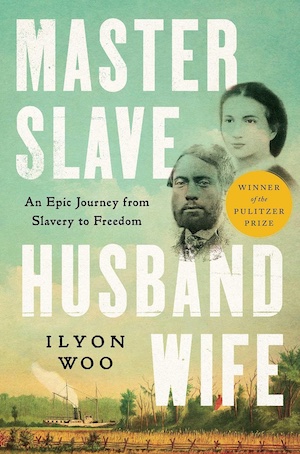

The accolade “suspenseful” rarely features in scholarly reviews. However, it well describes Master Slave Husband Wife, by Ilyon Woo, the story of a black couple’s escape from slavery—a narrative which is also vivid, and imaginative, and scholarly.

Five days before Christmas 1848, William Craft and Ellen Craft embarked on one of the slavery era’s most audacious flights to freedom. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, in their dashes from Maryland to Pennsylvania, each covered a hundred miles (Tubman on foot, Douglass by railroad). William and Ellen covered a thousand miles, by rail lines and coastal steamer, from Macon, Georgia, to the haven of Philadelphia.

William was tall, dark-skinned, a skilled cabinetmaker; he knew town life and hotel routine and railroad timetables, enough to plan an escape route. Ellen was petite and pretty, so light-skinned she could pass for white—but she could not write. She slathered on poultices, bandaged her jaw, bound her right arm in a sling (she hoped clerks would sign her name), donned green spectacles, and set out as an infirm young planter, seeking medical care in Philadelphia, accompanied by a tall, dark, devoted black body-servant.

Woo has a particular eye for detail. Unlike most slaves, she points out, William and Ellen had a vital corner of privacy. Ellen’s cabin had a door that locked, and William had built her a desk with a secret drawer. There they hoarded cash and men’s clothing—possibly also the pistol that William carried. With Christmas near, the couple were able to get slave passes to visit relatives. That gave them cover on the first stage of their escape, and possibly delayed discovery of their flight. Even so, they were nearly caught. Ellen drew attention, not least when she feigned deafness; a fellow-traveler archly quipped that the languishing young gentleman must be “either a woman or a genius.”

By the dawn of Christmas Eve, they had reached Philadelphia. There they sheltered with a Quaker family —and, for the first time, met white people who treated them as equals.

As well as the slavery regime of the South, with its slave jails and checkpoints, this book sketches deftly the turmoil of the North. Color prejudice could be harsh; on Cape Cod, abolitionist speakers were mobbed. But despite its contentious cliques and celebrities (Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison were falling out), freedom had a solid core of support, in Boston’s African Meeting House and the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Moving across this political landscape, Ellen and William covered another thousand miles, telling their story at abolitionist meetings. They were supported by best-selling author and progressive empresario William Wells Brown, who had himself escaped slavery, and was always ready to put a new fugitive in the public eye.

When slavecatchers tracked them down, William and Ellen were alarmed by these ruffians—but they were almost overwhelmed by the ardor of their friends. Their allies went to court for them, sneaked them across town, brandished pistols, harassed and mocked and sicced constables on their pursuers. Fiercely but presumptuously, their “rogue lawyers” proposed a last-ditch strategy for keeping them in Boston: since they had never been formally married, William could be arrested for fornication, putting him safely into the hands of sympathetic jailers.

Mr. and Mrs. Craft, now safely married, quietly escaped from this uproar. A long third act brought a longer journey, to England and finally back to Reconstruction-era Georgia. En route, William served on a mission to end slavery in Dahomey, and Ellen may have met again her old mistress, who was also her half-sister.

But where Woo truly takes leave of the couple—and which, as much as any other passage, helped Master Slave Husband Wife win the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for biography—is in London, at the Crystal Palace, during the Great Exhibition of 1851. With William Wells Brown, William and Ellen approached the centerpiece of the United States pavilion. This was the celebrated nude statue of “The Greek Slave,” an American sculptor’s attack on Ottoman atrocities—a classicized marble denunciation of the degradation of maidenly purity.

Next to “The Greek Slave,” the one-time fugitives laid a pointed political cartoon from Punch, “The Virginian Slave”: another woman naked to the waist—but black, and exhibited on a pillar ornamented with fetters, whips, and the Stars and Stripes. The group silently dared any American defender of slavery to challenge them; none did; and then, very publicly, they toured the Great Exhibition.

“For six or seven hours, the walking exhibition continued . . . . They went unchecked, unstopped. No one expressed shock or disapproval at the sight of the mixed-race groupings. No one identified or hunted them down . . . . In the transparent world of the Crystal Palace, William, Ellen, and William Wells Brown were both visible and invisible.”

This was, Woo asserts, “the ultimate fugitive slave’s triumph.” “William and Ellen, Ellen and William, broke free of all encumbrances as they walked as global citizens: master slave, husband wife, no more.”

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) grew up in Mississippi and writes on Staten Island. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.