By Indira Ganesan

Shortlisted for the Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

Imagine a vast pond representing time or history. A series of stones are skillfully skipped to skim its surface a dozen times, leaving ripples that might intersect in its wake. One such stone might represent Greek thought from the fifth century, and we see it land in Plato’s time where he invented an entire history for Greece to simply compete with Egypt’s ancient history; we see it touch India where Asoka uses Greek language to inscribe his pillars; it lands in Nigeria where writer Wole Soyinka fuses Yoruba mythology with Greek theater to compose his plays in the 20th century. Another stone might be monotheism as envisioned by Queen Nefertiti, skimming across the earth with various stops.

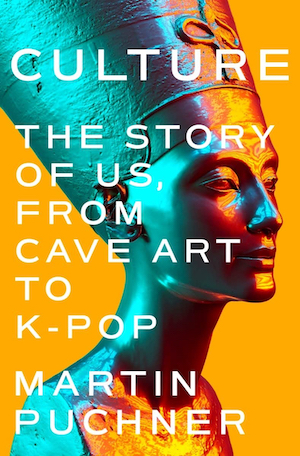

I use this image to describe Puchner’s enthusiastic romp through 40,000 years of earth’s history in Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop. Puchner, a former editor of The Norton Anthology of World Literature, offers the reader a sampling of moments of cultural borrowing and discovery, through individual and institutional methods of preservation and organization. With whimsical delight, he offers the reader a look at the Chauvet cave in France, exploring how it might have evolved as a refuge for bears, wolves, and ibex, to a place where human hunters and gatherers drew on its walls illustrations of those very animals, spurred by the tracks and markings left by the former inhabitants. For thousands of years, until a landslide sealed the cave, humans strove to improve these paintings, creating a wealth of artistry.

In Egypt, Nefertiti and her husband try to establish a monotheistic religion but fail in the attempt, possibly influencing a group of nomadic shepherds who are later led by Moses. A prince steals the Ark of the Covenant from his biological father, King Solomon, and brings home to Ethiopia a dynasty and a foundation of Christianity. In the 600s, a Chinese Buddhist monk goes to India to search for sources of his faith, encountering the gigantic stone Buddhas carved into the mountainside in present-day Afghanistan. The image of the statues destroyed by the Taliban in 2001 is reprinted in this book, bringing back the haunting sense of loss that I felt on seeing the photographs in The New York Times back then. I digress, but I am grateful for the reminder that Puchner gives me of how important our cultural artifacts are, how connected I felt to stone carvings erected thousands of years before I was born and had never seen in real life.

I do have a bone to pick with the author about the title, though. A marketer must have suggested the title for the catchy alliteration because it has little if anything to do with K-Pop. Sadly, K-Pop was the reason I picked up the book, but the subject is dismissed with a few not fully researched lines in the epilogue. For a better analysis of K-Pop, I suggest Hallayu!: The Korean Wave by Rosalie Kim, a catalog of the recent exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Frankly, Culture: The Story of Us is a fine title on its own, not needing any further clarification.

But let us return to those first cave artists who drew on the walls of the Chauvet caves. They went to the caves, says Puchner, “to create their own version of reality . . . to make sense of life in the outside world . . . to make meaning.” The history of culture is to seek “the story of know-why,” says Puchner, and thus he offers us a series of examples of heroic undertakings to make sense of our world, to create “the story of us.” This plurality drives the thesis, though he acknowledges the attempt to get at meaning can wreak havoc and destruction along the way.

Using the examples of translators and writers, Puchner underscores the importance of recording cultural history, while celebrating the means we have of storing the information. This is what we do in the present time in using social media to record our movements in real-time. To this end, the Future Library project invited prominent writers to author works that will be sealed in the Oslo Public Library until 2114, where they will be, as Puchner informs us, printed on paper made from trees planted as saplings in 2014. One of the writers, Han Kang, who recently won the Nobel Prize for Literature, expressed sorrow that these trees must be felled to accommodate the project, which brings up our age-old pattern of violence, through colonialism and warfare, to intersect with other cultures, resulting in what might be an appreciation through possession of those conquered. Puchner is quick to acknowledge our failings as a society throughout history, even amid the heroic rescues and retention of cultural thought.

Culture: The Story of Us is a garland of informative digressions. As with the Norton Anthology, a reader might jot down the subjects they are most interested in to do further research. One might note to oneself to read Middlemarch; seek out Sei Shonagon; learn more about the circular city of knowledge, Baghdad, and its glorious collection of translations from the Greek. One might also take a listen to Puchner’s talks and interviews on YouTube. It is a vast topic, culture, and Martin Puchner’s most recent book is an effective guide.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).