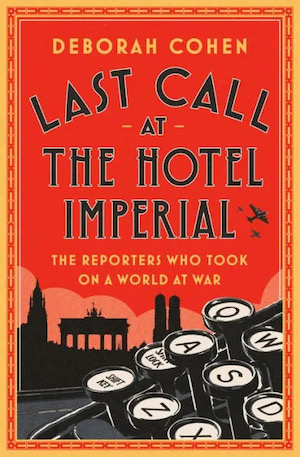

Winner of the 2023 Phi Beta Kappa Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

By Allen D. Boyer

“Notes scribbled in little spiral-bound books as they were interviewing Hitler, Gandhi, and Mussolini. Letters to and from lovers . . . . Diaries of rigorous, chiding introspection, full of desires and jealousies and gossip. Volumes of dream journals kept at the behest of a psychoanalyst . . . . Thousands and thousands of candy-hued slips of paper, bound together with rusty paper clips or stuffed into envelopes. On one scrap, a confession of infidelity, on another, a rumor about Stalin’s family life.”

From the archives of the great age of American journalism, with the quick cuts of a newsreel, backed by the clacking of typewriters and the hum of a shortwave radio, Deborah Cohen (ΦBK, Radcliffe College) offers a marvelous group portrait of the American foreign correspondents who reported on Europe in the years between the wars.

Dorothy Thompson numbered among her husbands Sinclair Lewis. A cross between “the Goddess Minerva and the engines of the S.S. Normandie” (as John Gunther put it), she was the first American reporter expelled from Nazi Germany—after Hitler came to power, for a long-past interview in which she had called him “an agitator of genius,” yet soft-mannered, “almost feminine.”

Jimmy Sheean, the University of Chicago man at the upstart New York Daily News, once counted up the places he could never go back to: Paris, Prague, Shanghai, Singapore, Lake Maggiore, Barcelona, Munich, Salzburg, Rangoon, Athens.

Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker could swear in every major language but always carried a Bible (back home in Texas, his father was a Methodist preacher). Knick wrote for the Hearst syndicate, when he wasn’t drinking; he won a Pulitzer for reporting on a 10,000-mile journey across Stalin’s Russia.

Emily “Mickey” Hahn went to earth in Shanghai, smoking opium and filing stories for The New Yorker. John Gunther and Frances Gunther juggled a marriage burdened with lovers and family losses. Young Bill Shirer trailed John and chased Frances.

“The leading lights of international reporting didn’t come from the boarding schools of the East Coast or the Ivy League,” Cohen writes. “Rather, they hailed from America’s Babbitt towns and the rich agricultural plains of the Midwest, the provincial heartland. The revolutionary changes in technology and transport that brought Model Ts to rural Americans also delivered mail-order books . . . as well as the big-city papers that traveled hundreds of miles through the night to be delivered before breakfast.”

In the ‘20s and ‘30s, American correspondents dominated world news. With America’s best young novelists working from Paris and its businesses tied to a new global economy (the bank failures of the Depression started with the collapse of Austria’s Credit Anstalt), the nation’s newspapers sent out journalists to cover the world, paying for assignments that European papers could not afford. “The American type of wandering or perambulatory foreign correspondent,” Harold Nicolson commented, was a Yankee innovation that the British should imitate.

In Vienna, at the Hotel Imperial, the foreign correspondents took over the café.

“There was an aroma of conspiracy about the place; it was said that the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been plotted there. A white-gloved waiter oversaw the wooden cupboard in which 16 Austrian newspapers and 60-odd foreign papers hung on rattan racks: Yugoslav and Bulgarian broadsheets; newspapers from Greece, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark and a Cairo paper published in English.”

Last Call at the Hotel Imperial has something about it of The Front Page, in which Chicago newsmen compete and collude to land a scoop and do justice (and playwright Ben Hecht floats across this book in a recurring cameo part). But peering below the surface, Cohen argues that the correspondents’ careers reflected a conscious blurring of the personal and the political.

Interviewing dictators was a way to write about the political conflagrations that were kindling across Europe. Like others of their age, the correspondents found in psychoanalysis a theory to connect private experience with public events. John Gunther tried to win an interview with Sigmund Freud by offering new details of Hitler’s family background, and Frances Gunther was even more strident. “Tear the veil off the dictators, she urged her husband.” Write “that Poland’s Marshal Pilsudski was subject to psychopathic temper tantrums and Turkey’s Kemal Atatürk was a mother-fixated drunk.”

The stories the correspondents filed were not the self-dramatizing narratives of 1960s New Journalism, or the identity-grounded nonfiction of the present day. Rather, “they wrote what they thought about the events in Europe and Asia and, just as importantly, what they felt. The truth, as Jimmy [Sheean] put it, mattered more than a litany of facts. For Americans, it required a new way of imagining oneself in the world.”

“Even when they were far part, even after they fell out, they kept right on talking and arguing, long after the actual conversations had ended.” That is Cohen’s epitaph on her characters. Keen-eyed, quick-witted, sharp-tongued, ambitious, persistent—perhaps the crowd at the Hotel Imperial was America’s answer to Bloomsbury. It’s a great story, and Cohen tells it well.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) is a writer and reviewer, a native of Mississippi working on Staten Island. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.