By Allen D. Boyer

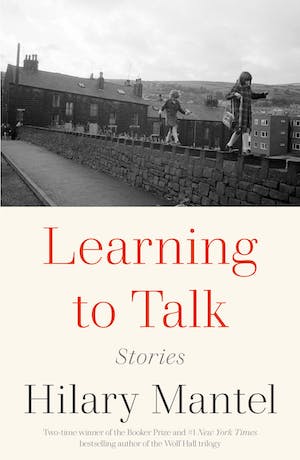

The sad, sudden death of Hilary Mantel deepens the timbre of her final published book, Learning to Talk. The stories and memories collected here deal with Mantel’s childhood in northern England—starting with a village in the Peak District, a place “of soot-blackened textile mills, with steep streets lined by small cold terraced houses,” “just out of the curl of the city’s tentacles.”

In this book, there are no crystal-clear recollections of epiphanies or crucial forks in the road. Instead, Mantel recalls childhood as a time of struggling to learn, simultaneously, what words meant and what the reality behind those words might be.

“Next door to us in the row lived my aunt Connie. She was really my cousin, but I called her aunt because of her age. . . Connie was a widow. I thought she always had been. Until I was older I didn’t know ‘widow’ meant a husband had once been there. Poor Connie, people said, the loss of her faithful dog is another blow to her.”

The milestones of this remembered childhood are moves from one school to another, from one house to another, from life with her mother and father to life with her mother and a new man. The lodger, Mantel calls him in one story: “He brought home in his pay packets more money than we had ever had in the house, and whereas when he came at first he would hand over his rent money, now he dropped the whole packet on the table.”

Occasionally, these stories suggest whom their narrator would grow up to be. Behind the novelist who wrote of Robespierre is the teenager who checked out “seven big books at a time about Latin American revolutions.” When the author of Wolf Hall visits her home village, she notes the unused schoolhouse and the empty convent.

“King Billy” is about a neighbor’s breakdown. “Curved Is the Line of Beauty” recalls what it was like, in an all-white region, to meet someone who wasn’t. In “Third Floor Rising,” Mantel remembers her mother’s late-blooming career as the boss in the ladies-wear section of a small Manchester department store.

The title story, “Learning to Talk,” focuses on the desperate English obsession with class and accent. Mantel was tutored by a shopkeeper-elocutionist who sold knitting wool and baby clothes and once had played Lady Macbeth. The curriculum featured rhyming tongue-twisters designed to suppress regional accents—not quite successfully. Mantel recalls:

“My brothers and I had often been baffled, when we were first translated to Cheshire. ‘What do they mean,’ asked the youngest, now at a Church of England school, ‘when they talk about the Kingdom, the par and the glory?’ And for years I thought you could win a point at tennis with a well-executed parsing shot.”

Mantel was born in 1952, but only rarely does recent history intrude on these stories. Mantel recalls playing at being an atom bomb spy. From Ulster, the Troubles echo in a village feud. The Moors Murders set the stage for one tale, although it is not on a featureless moor that the characters lose themselves, but inside a junkyard maze of wrecked cars. Rather, these stories feature the timeless: the bleak landscape that frames Wuthering Heights and Game of Thrones, the perennial English quest for respectability, the eternal frictions of family life. It comes almost as a shock when Mantel mentions her mother’s cold kitchen, “warmed only by the glow of her Elvis poster.”

These stories take place in the era of Swinging London, of Carnaby Street and Mods and Rockers and the Jaguar XKE and the Beatles—but all that lay far south of young Hilary Mantel’s world. The only Beatles song that matches these stories, in its taut, somber eloquence, is “Eleanor Rigby.”

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) lives on Staten Island and is working on a history of the law of treason in England. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.