By D.T. Siebert

“It’s the power of Casanova’s story as a story—the seductions and affairs, the scams, the impersonations, the joie de vivre, the enormous risks and hair-raising escapes, the lifelong struggle to invent and reinvent himself, and the shocking discovery of what it feels like to wear the mask of aging—that remains unforgettable. We know more in more depth, than we do about almost anyone who lived long ago. The Histoire de Ma Vie [History of My Life] conjures a world that was once as alive as ours is now, and we travel through it with a storyteller who opens the world to our minds, senses, and feelings. It is a book of life.”

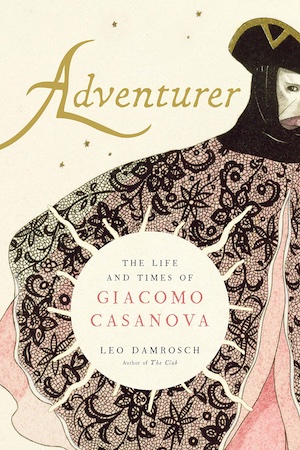

These are the closing words of Leo Damrosch’s superb biography of Giocomo Casanova. What Damrosch says here applies as well to his own retelling of Casanova’s story. Damrosch has written other remarkable books—about Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jonathan Swift, Blake, Samuel Johnson’s Club, and others—but this book may eclipse them.

A mass of scholarly research stands behind Damrosch’s book, including generous quotations from Casanova’s voluminous autobiography. Nonetheless, readers might often find the book like reading a picaro’s tale—one full of excitement and adventure.

To no one’s surprise, the spiciest parts of the book reveal Casanova, the master seducer, adventurer, and libertine—or chameleon in mask—as his whole life might define him. Damrosch observes that some stories of his sexual conquests might resemble “fabliau right out of Boccaccio or Chaucer.” One of the earliest is the seduction of a young and pretty bride. At the wedding reception, the bride seems jealous of her groom’s attention to her sister. Then, a day or two later, the bride and Casanova find themselves in a carriage, returning from a neighboring estate. A violent thunderstorm occurs. Terrified, the bride clasps Casanova and then jumps onto his lap. What ensues is easily imagined. The next day the bride reproaches Casanova, tearfully accusing him of ruining her. But soon, with a coy wink she admits forgiving him for her stolen pleasure.

Casanova’s seductions often seem almost philanthropic, at least to him. They save repressed devotees from straitened religious and moral scruples, while providing them with a liberating dose of intrigue and pleasure in the bargain.

When crossed, however, Casanova can be inventive in revenge. When he realizes at one point he is being strung on, paying for future pleasure by a mother and her beautiful daughter, he buys a parrot and teaches it to repeat, “Miss Charpillon est plus putain que sa mere”—”Miss Charpillon is more of a whore than her mother.” Then he sends his servant out to the markets to sell the bird at a price no one will pay. But the parrot does its duty in publicly shaming the two women. It’s almost like an audible graffito.

Among the many erotic adventures, there is this remarkable one. In Italy at the time, a casino was a kind of apartment designed for voluptuous assignations—furnished with erotic pictures, and fitted with secret eye holes in the walls. A nobleman lends his casino to Casanova—and his mistress, too. A dinner worthy of Apicius—complete with oysters sine qua non—arrives via dumbwaiter (no servants are present). Then, while the nobleman watches through the peep holes, Casanova and the mistress put on a pornographic show, well-calculated to excite his jaded and probably flagging priapic powers. Of course the performers know who is secretly watching them.

A man who regards seducing women as both his vocation and avocation might not be celebrated today. Faced with this problem, Damrosch reproves his subject’s obsessive-compulsive tomcatting, while reminding us that this was another age. Indeed it was.

Lest we conclude, however, that Casanova was little else than a notorious seducer and scam artist, Damrosch reminds us that Casanova was an extremely talented, intelligent man—one with initial ordinations in the Church and a Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Padua. He was accomplished in mathematics. He had a natural ability to acquire languages, both ancient and modern. He translated Homer’s Iliad into Italian. His precocious knowledge of Latin once astounded his company. One gentleman asked him to explain a riddle about grammatical gender—that is, when in some languages declined gender does not coincide with actual gender. [Note: The following was spoken in Latin]: Why in Latin is penis feminine in grammar while vagina is grammatically masculine? Casanova’s answer: Because the slave takes the name of his master. This, from a boy in his pubescence.

Nor does Cavanova’s life lack old-fashioned, hair-raising adventure, a la James Bond—some not even connected with erotic intrigue. Damrosch devotes a whole chapter to our rogue’s escape from imprisonment in the Venetian Doge’s prison, atop the ducal palace. No one had ever escaped from the prison before. That challenge didn’t deter Casanova. He was, to say the least, a man of action. He and a fellow prisoner managed to drill their way up through the leaden roof of the prison, only to discover they couldn’t rope down from the slippery roof, with guards stationed below. So they made their way back inside the ducal palace itself and managed to summon an outside guard, who let them out, assuming they were late-night revelers. Then a hired gondola brought them to safety on the mainland, away from Venetian authority. (Read Damrosch’s fast-paced narration.)

Among numerous other things to praise are Damrosch’s many illustrations. They bring us closer to the dramatis personae and the scenes of the drama. And it’s a delight to read the many proverbs and aphorisms Damrosch includes—from the ancients to the moderns, both bawdy and profound

Prompted by Damrosch’s biography, a recent article about Casanova appeared in the June 27, 2022, issue of The New Yorker, written with verve by Judith Thurman.

D.T. Siebert (Phi Beta Kappa,1962, University of Oklahoma) is Distinguished Professor of English Literature Emeritus at the University of South Carolina.

Author Leo Damrosch is a Phi Beta Kappa member from Yale University, where he was inducted in 1962.