By Marina Catullo

In Jory Fleming’s childhood home, there was a small cassette player. On quiet evenings, his mom used to ask him if he would like to listen to his music. He would reply, ‘It’s a cold night.’ She would respond, then ask again if he’d like to listen to music. He would reply again, ‘It’s a cold night.’ Initially confused, his mom eventually realized that at one point in time she must have commented, ‘It’s a cold night,’ and then started the cassette player. Fleming’s mind then made a connection between the sentence, ‘It’s a cold night,’ and the cassette player playing music. “His brain had put words together and made a connection, but it was a connection that no one else got,” Kelly Fleming said.

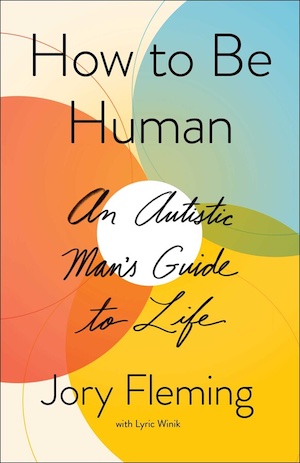

This is one of many examples of the way Fleming’s mind works, as detailed in his book, How to Be Human: An Autistic Man’s Guide to Life (Simon & Schuster, 2021). Diagnosed with autism at age five, Fleming (ΦBK, University of South Carolina) struggled in classrooms designed to favor neurotypical brains. Fleming had been enrolled in an autism program in kindergarten, but the program was disbanded after just one year. Following many stressful months of sensory overload, Fleming’s mother decided to pull Jory out of public school and homeschool him. Even though this new environment led to steady improvements in Fleming’s learning, it was unclear if Fleming would graduate high school, let alone become the first person with autism to be awarded the prestigious Rhodes Scholarship. As a Rhode Scholar, Fleming completed a master’s degree in environmental change and management at the University of Oxford and is currently a senior research associate and adjunct professor in the University of South Carolina’s geography department.

After being selected as a Rhodes Scholar, Fleming made headlines. He was profiled in The Wall Street Journal and interviewed on NBC. This influx of media attention came with offers for Fleming to sign over the copyright for his life story. Initially overwhelmed by these offers, Fleming followed advice from his mentors, who helped him to understand why people might want to hear his story. “It’s kind of hard to think about yourself as an object of interest,” Fleming mused. “It’s just that the way that my brain works, and the way that I think, and the way that I interact with environments has always been a part of my life. And I hadn’t really reflected that people outside of those that I knew in person would be potentially interested in learning about that.”

How to Be Human is written as a series of conversations between Fleming and writer Lyric Winik. Through these conversations, Fleming and Winik explore what it is like to live in a world constructed for neurotypical brains when yours is not and, ultimately, what it means to be human. While the book provides a window into Fleming’s interior life, it’s not a guide to everything there is to know about autistic people. Fleming questions if a book like that could, or should, exist, as these caricatures often erase or gloss over the varied realities of individual autistic people. “I think it can be a really helpful exercise sometimes to think about what people share in common, but it can be equally helpful to think about how individuals can be different. And I know that from my own interactions with other people who are neurodiverse,” Fleming reflected. “We’re different people.”

Fleming does hope that by giving people insight into the way his mind works, they can extend that knowledge to people they may know who are neurodiverse. And, perhaps, extend more empathy and understanding towards people they don’t know. For example, if you encounter Fleming singing to his service dog, Daisy, in the grocery store, try to refrain from making any negative assumptions. Fleming believes that when we take the time to learn about other people rather than judging them, it’s often a rewarding experience.

Fleming himself strives to be a lifelong learner. Be it auditing liberal arts classes or talking with people who view the world a bit differently than he does, Fleming is always looking to expand his horizons, and he encourages others to do the same. “I think that’s within all of our capabilities, whether you’re a member of Phi Beta Kappa or not. Whether you’ve gone to college or not. You can always learn something new if you’re willing to listen.”

Marina Catullo is a graduate of the University of South Carolina where she studied political science and English. She was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa there in April 2021. The University of South Carolina is home to the Alpha of South Carolina chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.