Shortlisted for the 2020 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award

By Allen D. Boyer

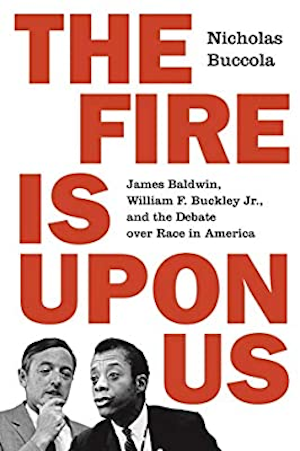

Nicholas Buccola has written a marvelous dual biography of two American writers who engaged forcefully during the racial turbulence of the 1960s: a bitter, clear-eyed insurgent and a gifted, willful popinjay, James Baldwin and William F. Buckley.

By 1965, the year on which this book turns, Baldwin had been a charismatic teenage preacher—thrown a mug at a white waitress in a diner, when she announced that “we don’t serve Negroes”—begun reviewing and writing—and worked his way into the pages of Partisan Review and The New Yorker. In the end, Baldwin had understood and forgiven the mass of white citizens who lived day-to-day lives in a segregated society, saving his scorn for intellectuals who understood and yet failed to denounce Jim Crow.

In the same years, while Baldwin was writing the essays that became Notes of a Native Son (1955) and The Fire Next Time (1963), Buckley kept a measured distance from racial issues—just within sniping range. He authored a book that faulted Yale for lacking godliness, co-authored a book that faulted the American establishment for mistreating Senator Joseph McCarthy, and ended by founding a magazine, National Review, meant to “stand athwart history, yelling Stop.” At every juncture, Buccola argues, Buckley put himself among the public intellectuals whom Baldwin scorned.

In a 1957 National Review editorial, “Why the South Must Prevail,” Buckley favored a slow enlargement of black people’s civil rights, managed from above by judicious, prosperous white men. “The central question” in the South, he thought, was whether the Southern white community was “entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not dominate numerically.” Eight years later, in a column titled “How to Help the Negro,” he insisted on another distinction. As Buccola sums up, Buckley maintained that “there are disreputable ‘primitives’ whose support for segregation is rooted in racial animus, and there are respectable conservatives who are ‘opposed to coercive integration’ as a matter of principle.’”

The centerpiece of the book is the Cambridge Union Debate, on February 18, 1965, where Baldwin and Buckley faced off before a crowd of English collegians. The motion debated was whether “the American dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” Baldwin spoke first, and pithily.

“It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you.”

“If those [were] white people being murdered in work farms, being carried off to jail, if those [were] white children running up and down the streets, the government would find some way of doing something about it.”

“I am not a ward of America, I am not an object of missionary charity, I am one of the people who built the country. Until this moment there is scarcely any hope for the American dream because the people who are denied participation it, by their very presence will wreck it. And if that happens, it’s a very grave moment for the West.”

The audience gave Baldwin a standing ovation. Buckley waited it out, and then began. He opened by claiming that Baldwin, in The Fire Next Time, had “threatened America with the necessity for us to jettison our entire civilization.” He ended with the same point, having used the phrases “unctuous servitude,” “luridities of oppression,” “endogamous instinct,” and “immanentize our own misgivings.”

Of the Union members voting, 544 agreed with Baldwin that the American dream came at the expense of the American Negro. Buckley won only 164 votes; but he was unfazed. Two months later—just after “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, when Alabama state troopers and deputies charged black protest marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge—Buckley spoke to six thousand New York City policemen at a Holy Name Society breakfast. With appalling irony, he praised the “restraint” shown by the Alabama lawmen. Before they charged with clubs and police dogs, he observed, they had waited in orderly ranks, “until the human cordite was touched—who threw the lighted match?

Buckley’s self-confidence proved irredeemable. Not until 2004, and only obliquely, would he regret having served as an apologist for segregation. (“I once believed we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow,” he told a journalist. “I was wrong; federal intervention was necessary.”)

If Baldwin’s truths made his audience uncomfortable, this book suggests, was this not because those truths were so hard-won—because he himself was uncomfortable with them? And if Buckley spoke of racism in latinate terms and circumlocutions, was this because he hoped to mask the fact that he was serving the cause of segregation? He hardly distanced himself from the problem, and he clearly distanced himself from any solution.

Buckley’s genteel phrases rarely yield heat or light. Baldwin’s writing still generates both. It is with Baldwin that Buccola’s sympathies lie, and whose case is supported by the volume of material that this book marshals.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University) is a writer and reviewer living in New York City. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.