By Allen D. Boyer

Svetlana Alpers, a distinguished scholar of European painting (and a frequent reviewer for The Key Reporter) turns her formidable attention to a reader of Flaubert and Baudelaire, a student of Atget, and a bon-homme who spoke with a Parisian accent: Walker Evans, a photographer whose images seem archetypally American. The resulting volume is a learned, suggestive, and handsome work.

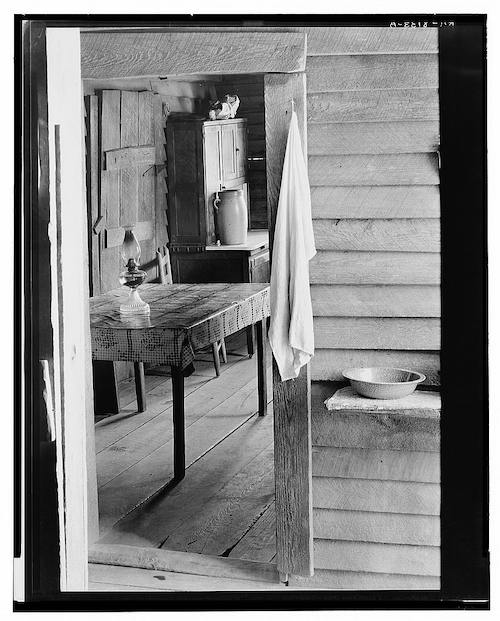

Alpers studies Evans’s work employing the techniques used to critique paintings: by assessing how he framed his scenes, in the light of his printed statements and off-the-cuff remarks. Her most illuminating is the theme of detail. She focuses on what Evans focused on.

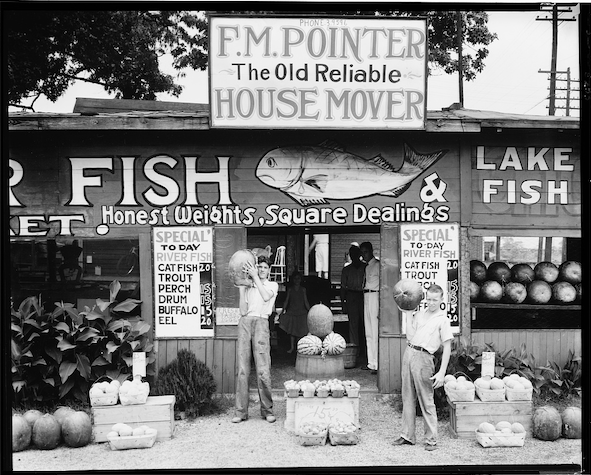

“A garbage can, occasionally, to me at least, can be beautiful,” Evans remarked. Nora Sayre, the film critic, recalled what it was like to walk through the city with Evans: “He would seize my shoulders—‘Look!’—and wheel me around to focus on whatever he’d just seen . . . a Victorian lamppost or the texture of old stone, a batch of secondhand bathtubs for sale on a sidewalk, the juxtaposition of several buildings.” Perhaps a fondness for detail should be expected from a man who hoarded photo postcards. (Evans’s archive of 9,000 postcards is now held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Evans scrupulously recorded the place and time at which he made his photos—but, apparently, neither site nor date controlled how he viewed his works. “He did not exhibit or print photographs grouped according to where they were made,” Alpers observes.

Evans’s photographs, Alpers finds, are like the sketches in Cézanne’s notebooks. They feature images that may be parts of larger scenes, but they are never fragments. Nor are they studies. “They are not preparatory for paintings, but for seeing [and] thinking . . . . Playfully, we might invert the comparison: the multiple observations collected on Cézanne’s carnet pages remind us of Evans, himself an avid collector.”

Such comparisons might be pushed farther. Evans did not simply produce details; he shaped images. He went beyond cropping photos; he would cut down a negative. This radicalism is as sharp and clarifying as Gauguin’s remark that if a shadow looks blue, the artist should paint it blue.

Alpers locates Evans in an ironic but quintessentially American context. For thirty years, Evans worked in the world of corporate publishing—for Time and Fortune magazines, first on assignment, later as a special photographic editor. He left Fortune to lecture at Yale. Evans’s work from that period is little-known, buried in articles in individual monthly issues of Fortune. Much of that work is in color; its broader study (begun by Leslie Baier) might change our impression of an artist known as a master, and a champion, of the black-and-white print (so might further study of Evans’s last period of work, the years when he left behind his Rolleiflex and tripod, put down his 35mm Leica, and avidly took up the SX-70 Polaroid).

Alpers also reframes the reputation that Evans earned as a photographer during the Depression. For most who know Evans’s work, it is these photos—the rural photos Evans took for the Farm Security Administration, the studies of Alabama sharecroppers from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the scenes published in American Photographs (1938)—that will come first to mind.

Evans knew that he was known for these photos. He did not want to be remembered for the wrong reasons. He objected: “I’ve certainly suffered when philistines look at certain works of mine having to do with the past, and remark, Oh how nostalgic—I hate that word.” That gripe went with a broader warning: “A sense of the past and a sense of history is not nostalgia. Nostalgia has become debased to mean a kind of syrup savored by self-pitying people conjuring better days, funny hats, and an innocence that nobody ever had.”

Those words are as clear-eyed as Evans’s photos. They are a sharp reminder that history is more than people comfortably make of it.

Allen D. Boyer (ΦBK, Vanderbilt University), a native of Oxford, Mississippi, works and writes on Staten Island. Vanderbilt University is home to the Alpha of Tennessee chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.