By David Madden

The grave of the mother of poet Natasha Trethewey has “remained unmarked by a headstone” in Gulfport, Mississippi, since she was murdered 35 years ago.

Beginning in 2000 with the first of her six books, Trethewey has included numerous lines of her own poetry that constitute metaphorical epitaphs, tributes to her mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough. She brings the words “memorial” and “monument” into play with poignant irony. For 12 years, Natasha, her mother, and her mother’s killer lived on Memorial Drive outside Atlanta, with a view of the famous carvings of Confederate leaders Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson, called “the largest shrine to white supremacy in the history of the world.” The very title of her 2018 collection Monument: Poems New and Selected also suggests a perspective on her writings as a composite homage. Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir is richest and most moving if read in the complex context of all her preceding works.

In a sustained lyrical style, Memorial Drive is an impressionistic meditation on her mother’s life and its effect upon her own. Gwendolyn was born in New Orleans in 1944 and raised in North Gulfport. Her father left her. “I grew up knowing,” says Natasha, “that my mother’s life began with abandonment.” In Gulfport, Natasha and her mother knew the “comfort of a small enclave of close relations.” Gwendolyn was “personnel director for human resources at the county mental health facility.”

Gwendolyn met Natasha’s father “in a literature class on modern drama.” Eric Trethewey, a native of Nova Scotia, author of six books of poetry, wrote poems about Natasha, beginning with “Her Swing” in Dreaming of Rivers (1984). “I study my crossbreed child . . . My black wife watching from the house.” In “fictional accounts of their lives,” he called her Cassandra. But she was the reverse of Cassandra, hoping what she predicted would not happen if she kept silent. Though “My father believed in the idea of living dangerously . . . my mother knew the necessity of dissembling.”

In Atlanta, having married her second husband, Joel Grimmette, Gwendolyn was “on the cusp of her new life.” While she worked on a master’s in social work, Joel, who was convinced he had “the soul of an artist,” enrolled in a technical school. At the Mine Shaft restaurant in Underground Atlanta, Gwendolyn worked nights as a cocktail waitress in a sexy outfit that included “a heavy brass bullet belt, her body ringed in the objects of her undoing . . . bending to kiss her goodbye.” Natasha’s “mother’s true face, like her thoughts,” was “mostly hidden” from her. “It is no longer just the two of us . . . I am beginning to distance myself, to inhabit the periphery of my mother’s new life.” As a reverse Cassandra, Natasha did not then talk about and later tried to forget the years living in Atlanta, from 1973 to the murder of her mother in 1985.

Natasha’s own life was mostly interior, as she tried to please her remote mother. Intrusive scenes in her bedroom and forced rides in the car dramatize her own relationship with her mentally abusive stepfather, Joel.

As Cassandra, the internationally celebrated poet Natasha Trethewey conveys her mother’s tortured voice, inserting in full a written record Gwendolyn kept near the end of her life of Joel’s violent physical and demeaning mental abuse. Trethewey includes a statement taken at the police station, and the long transcription of Gwendolyn’s telephone conversations with Joel that she secretly recorded at the suggestion of the police—interrupted by a brief call from Natasha, the last time she heard her mother’s voice.

At trial, Grimmette said he intended to kill both mother and daughter, but when Natasha greeted him at a high school football game with a friendly “Hey, Big Joe!” he decided to kill only her mother that night. Trethewey has always felt guilty that saving her own life by greeting Joel, she somehow affected his murder of her mother.

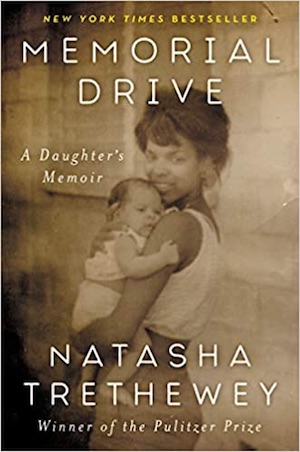

Trethewey includes no photographs. She relies upon “the power of metaphor” and provides a profusion of images. In the car on the road to Gulfport, her mother held her “so close we seemed conjoined, and I could feel her heart beating against me, as if I had not one but two.” She recalls an early memory: “My near drowning in Mexico, the image of my mother above me, arms outstretched, a corona of light around her face.” One of Grimmette’s two bullets “lodged near the base of her skull, behind the bloodred bloom of her birthmark.” “What I wanted to get rid of was that image of captivity and suffering, that final scream.”

Trethewey often hears her mother’s last question to her: “Do you know what it means to have a wound that never heals?”

The author of many poems, stories, novels, plays, and nonfiction, David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee) has just finished a memoir, My Creative Life in the Army.