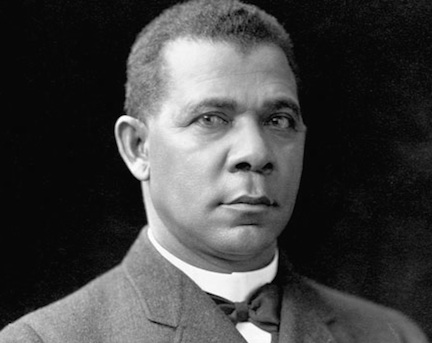

“I have learned that success is to be measured not so much

by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles

which he has overcome while trying to succeed.”

— Booker T. Washington

By Austin Harrison

“In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as fingers, yet as one hand in all things essential to mutual progress” was the famous line that lingered in the air during Booker T. Washington’s address to a crowd of predominantly white Southerners at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. This speech, later deemed the “1895 Atlanta Compromise,” was one of the most controversial social commentaries given before the turn of the 20th century and forever shaped Washington’s legacy in the eyes of history.

Washington’s background and upbringing are pivotal to fully understanding how and why he came to support economic progress at the cost of social stagnation. Washington was born on April 5, 1856 in Hale’s Ford, Virginia. As a member, and more importantly as a representative, of the last generation of black Americans who were born into slavery, Washington was heralded as the chief African American figure during his career. After emancipation, Washington taught himself to read. In his younger years, he worked in West Virginian salt mines to amass money. He then continued his education at the Hampton Institute and worked as a janitor to pay for his undergraduate education. After graduation, Hampton’s president recommended Washington to head the foundation of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881.

The Tuskegee Institute is one of Washington’s crowning achievements. When he accepted the invitation to head the institution, Washington was charged with literally building the edifices from the ground up. In fact for the first few years, all students participated in the construction of the classroom facilities, dormitories, and other university buildings, many of which are still in use today. The primary focus of the institute was to train future educators to go to other schools around the South and teach agricultural, industrial, and other technical trade skills to African American students. Washington dutifully served as the president of the institution until his death, 34 years later.

Washington’s philosophy concerning the progress of black Americans largely stemmed from his working class background. He saw vocational education and trade work as an easily accessible means to erect a black middle class. This economic stability would enable black Americans to fund the self-determination being pursued by others through political agitation. This method allowed for black progress without risking violent white backlash.

Part of his genius was his ability to appeal to, and be received by, a diverse range of audiences. For the Atlanta Compromise, he was selected to speak to a crowd of Southern whites at an event that attempted to highlight the progress the South had made both in industry and race-relations since emancipation. In his speech he assuaged their fears of blacks wanting full equality under the law, while simultaneously imploring the South to give African Americans the opportunity to “prove their worth” in the eyes of the South through hard work and model citizenship. Economic prosperity was, he perceived, the initial step to eventual political change for the betterment of black Americans.

One of the most common criticisms of Washington and his approach to progress is that he was not vocal nor outwardly supportive of political agitation and protest, unlike his contemporaries in the North. Though publicly this is accurate, privately he used the wealth he had accumulated over his career to clandestinely fund several efforts aimed at politically combating segregation, Jim Crow, and voter suppression across the nation.

In 1901, Washington became the first African American to be invited to the White House as a dinner guest. President Theodore Roosevelt welcomed Washington in order to consult with the most prominent African American voice of the time. This feat was all the more shocking considering that until Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, segregation was the law of the land. In fact white and colored only signs were part of the White House’s own décor. When he received the invitation, Washington knew that accepting it would be a giant, yet treacherous step for the progress of his race, because he would be opening a door that had previously been firmly shut to African Americans. Some people were so distraught by Roosevelt’s invitation to a person of color, that somebody hired an assassin to follow Washington back to Tuskegee. (http://www.npr.org/2012/05/14/152684575/teddy-roosevelts-shocking-dinner-with-washington).

After the death of Fredrick Douglass in 1895, Washington assumed the role of the foremost voice in the African American community until his own passing. In 1896, Washington received an honorary master’s from Harvard University, and in 1904 the Phi Beta Kappa chapter there inducted him as an honorary member. In 1901, Dartmouth awarded him an honorary doctorate. Omega Psi Phi fraternity recognized Washington for his works geared toward the advancement of African Americans in the educational, economic, and social realms. In the wake of his life and career, Washington left a legacy of unbroken barriers and a blueprint for the upward mobility of Southern blacks, arguably one of the most disenfranchised groups of Americans in the country’s history.

Austin P. Harrison is a junior at George Mason University majoring in environmental science with a concentration in conservation. George Mason is home to the Omicron of Virginia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.