By Svetlana Alpers

This is an interesting book in a number of ways.

It is interesting to read about an architect who did not want to make himself famous or more to the point who, though ambitious, was not into the self-display that was necessary to play the role of star architect in the 20th century—think Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, or Frank Gehry. Gordon Bunshaft was tense, boorish to other people, and did not want to put into words what he was about. Let the buildings speak for themselves was his view. The secrecy that Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the firm he worked for, insisted on when it came to revealing who the architect and designer were for their buildings fit Bunshaft’s nature, even as he chafed at it.

It is interesting to read about a time—mid-century America—when major companies had a belief in themselves and in America that they wanted to display in the form of the architecture of their offices and plants. Bunshaft worked for Lever Brothers, Pepsi-Cola, the Heinz Corporation, Reynolds Aluminum, IBM, and many insurance companies and banks. Half a century later, a number of the buildings have already been torn down. (Demolished followed by a date in parenthesis occurs often in the book.) As the world takes a global turn and business is more virtual than bricks and mortar, and as America’s sense that it is exemplary is no longer strong and clear, there is nothing in the corporate world to replace them. Museums are the major businesses hiring name architects today.

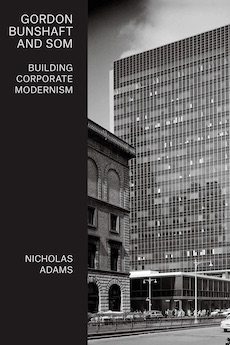

This book focuses on the work of Bunshaft (1909-1990) and the firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill for which he worked virtually all his professional life (1937-1979). It moves quickly from his birth in Rochester, New York, to his education at MIT, his travels in Europe, and then to his work. His signature building was done for Lever Brothers in 1952. Though it has been reconstituted over the years, it largely is as it started—raised and set back on a podium along Park Ave, with curtain walls of glass and steel. Bunshaft greatly disliked Mies van de Rohe, whose Seagram Building Bunshaft’s Lever House faces off against across Park Avenue.

He built Manufacturer’s Trust with its huge safe made magnificently visible behind a window on Fifth Avenue in 1954 and in 1960 a graceful headquarters for Pepsi-Cola on Park. The Lever building sticks in the mind, but the book has made one resident of New York (that is me) search about to find the Pepsi-Cola building (altered by an extension) and the bank. One is actually seduced into making such a search by the look the buildings have in the photographs made by the great Ezra Stoller who is now exhibited as a photographer in his own right. The consistently elegant look of Adams’ book is largely due to buildings as viewed by Ezra Stoller. One may well wonder in fact what is due to Bunshaft’s architecture and what to the exacting and riveting style of Stoller’s photographs.

Mid-career, Bunshaft made a change from sleek surface to plasticity or from steel and glass to concrete. In a certain way, the steady aestheticism of Stoller’s photographs diminishes (or is it moderates) this huge change in architectural style. In his photographs a new material elegance replaces the old. A landmark building in the new phase is the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale of 1963, followed in 1971 by the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. At the end of his active life—moving along as did the world—he designed an airport in Saudi Arabia and back home Lyndon Johnson’s monumental presidential library, and the huge, bent office building still looming at 9 West 57th Street.

An unexpected side of Bunshaft was his taste for finding art, notably works of sculpture, to go with his buildings. His favored artists—who it should be noted became close friends—were Isamu Noguchi, Henry Moore, Jean Dubuffet, and Alberto Giacometti. Back then, the corporate world went along with him. The splendid weekend house he designed for himself and his wife in East Hampton was a display place for a distinguished art collection (made beautiful for eternity by Ezra Stoller). Its fate was sad. The art he left to MoMA has been sold off. The house was bought by Martha Stewart who transferred it to her daughter who sold it to someone who demolished it.

Despite the presence maintained in Stoller’s photographs, the book gives us a look at time past. Today the buildings going up in New York City are skinny apartment buildings so tall that the global very rich can live safely above, free from the life of the city. Architecture is not a matter of interested public discussion as mid-century modern was. It is striking that no one has come along to replace the ongoing judgments of Ada Louise Huxtable.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.