By David Madden

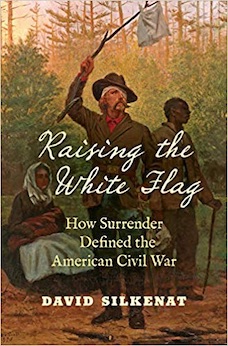

Among the increasing number of books that offer fresh perspectives on the Civil War, David Silkenat’s Raising the White Flag stands out as one of the most needfully illuminating.

Senior lecturer of American History at the University of Edinburgh, Silkenat examines the psychological and practical effects of surrender by one out of every four Union and Confederate soldiers upon every aspect of the four-year-long war, from Fort Sumter to Appomattox Courthouse. From individuals to groups, “Civil War soldiers surrendered at every level of military organization.” Almost as many surrendered as were killed.

In the tradition of earlier wars, most recently the Mexican-American, honor or shame defined whether soldiers were heroes or cowards, surrendering or deserting, in the first years of the Civil War. More and more, the question became the simple one of whether to fight and die or to surrender and live as a prisoner.

Silkenat makes policies of prisoner exchange and parole part of his study of this complex subject but does not consider retreat, which raises similar questions. He decided not to consider surrender at sea or the capitulation of whole cities, such as New Orleans.

The demand of unconditional surrender was often accepted when battles “to the last man” were characterized as being mass murder. But conditions in such prisons as at Andersonville produced fatal escape attempts and suicides.

One may imagine how the cumulative effect of Union surrenders must have influenced President Lincoln’s thoughts and feelings as he directed a war to keep the Union intact.

In the final months, “last ditch” battles encouraged surrender over futile resistance, resulting in the “convulsion” of surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

To insist that Silkenat should have ventured into the traumatic 12 years of Reconstruction is perhaps unfair. One may hope the prospect of doing that will prove intriguing to future “surrender” scholars.

In the South, suppressed guilt over treason and slavery, and the lingering sting of the shame of the final surrender inspired the cult of “the Lost Cause,” which restored honor by a sustained feat of rationalization that attributed victory to surrender. Silkenat declares that the South’s surrender assured the victory of emancipation.

Out of all the aspects of Silkenat’s useful study what now matters most is how the act of surrender affects the nation’s memory of the events and their long-term effects through the Civil War Centennial of 1964 and on through the Sesquicentennial of 2015 to the present era, as Confederate battle flags rise again and memorial statues fall.

David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee), LSU Robert Penn Warren Professor of Creative Writing Emeritus, is the author of The Tangled Web of the Civil War and Reconstruction. He is at work on Civil War Throughout History Worldwide.