By Indira Ganesan

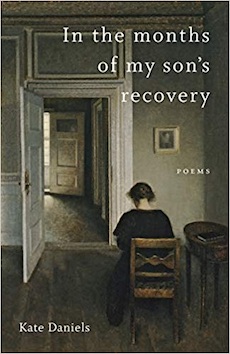

Kate Daniels new book of poems is an incandescent exploration of a woman’s rage and a mother’s fury, and the necessary acceptance of a life that includes contradiction. In the Months of my Son’s Recovery is an ode to menopause, to addiction, and a search for meaning in a crazed world. From the title of her opening poem, “Her Barbaric Yawp,” referencing Whitman, she sings in awe of “the aging Female Body”:

Young,

Clad all over in tight, unwrinkled skin, not yet

Stretched out or sagging, she was a pleasure

To ogle…so we gawked and gaped….

…. Well, that’s all decades in the past. Now,

There’s this flowing away…

And eating more salads, giving up

Hard cheese, or taking on red wine,

Even adding extra sessions of Pilates

Won‘t do a goddamn thing to change it.

Yet to quote fragments of her poems is really to do a disservice, as the beauty of a Daniels poem is in exactly how the words are chosen, and how they come together, cut with an Exacto knife, finessed with a broad scope of a poet’s tools. These are not pretty, decorous poems, but hard and harsh stares at reality, and breath-taking in their vigor and wisdom. Look at how the line breaks in each poem emphasize and underscore, how the humor is turned to irony, to sad profundity. To read only fragments (and fragments are what I will offer here) is to hear a stifled scream, a half laugh, a chocked back cough. Thankfully, a review only points the way to the work itself.

Kate Daniel’s book is divided into three parts, and the first is “Her.” From the aging body, the astonishment of a body’s betrayal, and worse, society’s betrayal, we go back in time to the annihilating ways in which young girls try to control their bodies and apologize for their minds as the author takes in student conferences (“This is probably wrong, she says. Probably/stupid, twisting her hair, and shrinking back”) to where as an experiment, the narrator, fresh out of college herself, undertakes to challenge the Male Gaze. Recalling her impulse to turn an assault into something poetic (because that was how we justified the world then) the narrator, in a sweet reversal, reading Frank O’Hara, ferries to Fire Island, where the Gaze flickers “neither dismissive nor predatory—nothing more than one person taking casual note of another.”

The next set of poems is called “The Addict’s Mother.” Into the mix of the ungainly beauty of an aging female body comes a child who has given himself to heroin addiction. Now come the sharp, blunt realities of a son who will steal a family car to trade for drugs, whose path of self-destruction can only make a mother look at herself to read the addiction that might have lain hidden. The mother character, who is an amalgamation of many mother, not just the poet herself, tries to find the meaning in the madness of bipolarity, or what Keats called negative capability.

The final parts offer the subject of recovery. Reading Thomas Jefferson’s biography gives the author solace and pause, opening up complexities that are ingrained in American life. She…

Can’t help drawing back at how he lived in two minds

Because he was of two minds like a person

With old-time Manic depression: the slaveholder

and Democrat, the tranquil hilltop of Monticello,

And the ringing cobblestones of Paris, France. The White

Wife, and the concubine: enslaved and black…

Daniels segues neatly into the birth of a son who carries the memories of genes and ancestors, how their tribulations and addictions are brought to bear on the present. “Even then, two minds circulated inside him” she says of her baby. Later, Daniels begins to reflect on how families cope with life-threatening situations (thank goodness for poets to render such words with sublimity!), ending with a poem I want to quote in its entirety, but feel, rather, you must read for yourselves. It is called “Yes,” and brings this heart-enlarging book to a wonderous close.

Novelist Indira Ganesan was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa at Vassar College in 1982. Her books include The Journey (Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), Inheritance (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998) and As Sweet As Honey (Alfred A. Knopf, 2013).