By David Madden

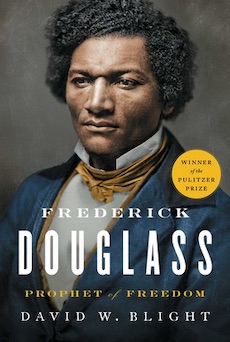

A few years ago, I listened to Yale Professor David Blight speak about his approach to the writing of his biography of Frederick Douglass. The enthralled audience agreed with me that he was one of the most natural, enthralling, and cogent speakers we had ever heard. Having read his Pulitzer-Prize-winning book, I can testify that as orator and writer wielding words, David Blight the biographer justifies comparison with Frederick Douglass, master orator and writer.

In eight pages, Blight brilliantly meshes his descriptions and effects of “What, to the Slave, Is the Fourth of July?” with quotations from it, creating a counterpoint of Douglass’ voice and his own. “Douglas channeled all his tension into a kind of music,” explains Blight. “His speech was like a symphony in three movements.” Douglass’ voice soared: “Above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are today rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them,” on this national day of celebration. The Old Testament was made flesh in the words he uttered.

Douglass told audiences “What the Black Man Wants.” His words have been quoted often: “Without a struggle, there can be no progress.”

Blight, whose own style is rousing, moving, and without decoration, makes a case for Douglass as a writer of pure literary distinction, observing: “He possessed a stunning ability with narrative.” Douglass’ second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, “more thorough and revealing” than his first, is “arguably the greatest of all slave narratives,” Blight observes.

Blight does justice to describing and analyzing the roles that many great men and women, friends and enemies, played in Douglass’ life. Ironically, both John Brown and President Lincoln were among his friends: “I could speak for the slave. John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave, John Brown could die for the slave.” About the Emancipation Proclamation, Douglass alternated between impatience and patience. The President “grows as the nation grows.” Some friends became enemies awhile, such as abolition leader William Lloyd Garrison and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a major leader in the universal suffrage movement. “My friends have brought me far more than my enemies have taken from me,” Douglass noted.

Blight masterfully maintains a fast-paced narrative, charging through a complexity of details. His chapter endings thrust the reader forward. Haiti “provided the elderly Douglass with one last opportunity to rock the world.”

Douglass held many positions. In 1899, he was the first African American to be appointed US Marshal and served in D.C.; later, he served as minister to Haiti during its revolution.

Blight leaves no aspect of Douglass’ life and legacy unexplored. In addition to being a brilliant orator, writer, and prophet, he was a social reformer, a politician, and a statesman who loved power. He was a radical, but he was pragmatic. Douglass was startlingly handsome, vain, arrogant, combative, ambitious, and self-reliant. He was spiritual and intellectual. He was an art patron, a music lover, a philanthropist, a born traveler, and often lonely. He was an advocate for civil liberties, emancipation, women’s rights, and black enlistment in the military. He worked hard for ratification of the 14th and 15th amendments. He urged and promoted civil war, calling it “far reaching and glorious” and “the school of affliction.”

Those aspects attracted many women, comrades, and lovers, four of whom worked to further his causes, one of whom lived in his own house with his family; another married him after his wife died. Douglass died at the age of 95 in Washington, D.C.

Mindful of the greatness of his own speeches and writings, I imagine Blight’s not minding much my ending with a few of Douglass’ immortal words: “The life of the nation is secure only while the nation is honest, truthful, and virtuous.”

Robert Penn Warren Professor Emeritus, LSU, David Madden (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979) is the author of books in many genres. His biography of James M. Cain, tough-guy novelist of the Thirties, is forthcoming.