By Svetlana Alpers

This book insists on the importance of old-time pleasures so rare today: the art is painting and sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, and the approach is a close looking at the making of that art in and of its circumstances. Starting from the subject of curtains, Paul Hills opened up to cloth in general. He takes off from the fine, expensive consumer goods used (often the same ones) in the daily life of homes, in the rituals of the church, and the celebratory décor of cities. There is an important visual point, a double point indeed. In its use, cloth marks a mutuality between persons and things that can be made visible in painting as it cannot be in words. Secondly, pictorial meaning arises from the making and perceiving of relationships such as these. It is not actual cloth, though its economic value and social use are fully acknowledged in the opening pages, but painted cloth which is the concern.

In addition to cloth and bodies the third central player in this book, as in the art it considers, is the materiality of the faith. We become conscious that veiling or clothing is a repeated image in the Judaeo-Christian tradition. It was a boon for artists that they saw and grabbed: the swaddling of the infant Christ, the veiling necessary in the presence of the divine, the shroud for death. In painting after painting we are led by Hills to look with newborn care and understanding at cloth. A conventional Alessio Baldovinetti Madonna and Child (1465) before a landscape contains wonders: the strand of swaddling cloth raised by Christ towards his mother’s womb, its pale course echoed and extended in a distant river; a gossamer linen veil over Mary’s head matched by another on the marble parapet touched by the Child so binding them together. Some pages later there is a foundational viewing of the handling of the color and the shape of drapery in a particular Bellini Madonna. You are made to feel you were right there as the painter took his decisions at work.

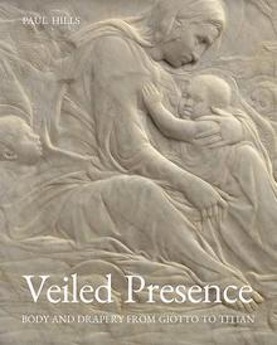

As Hills notes, while in painting the material of the paint that lies on the surface and that material of the support beneath it may be distinguished, in sculpture surface and support share the substance. A sculpted draped body brings into being a magical new entity: cloth and flesh at once there and not there. In the working of his Madonna of the Clouds (1425-35), Donatello adds clouds to the stuffs of flesh and cloth in worked marble. There is no way words could (or perhaps indeed should even try) to match the extraordinary complexity of Madonna, Child, and assembled angels that fill almost to bursting a small square shallow marble panel. Yet, in the end, it looks so simple and resolved.

Lorenzo Lotto is given a chapter of his own. A painter long seen as a bit of an outsider is here considered in terms of the drama he sees in and makes of drapery. A marvelous reading of his Christ taking Leave of his Mother (1521) focusses in on the fringe (for which Hills refers to the Old Testament) of Christ’s shawl. The scene takes place in a grand public hall, but Hills, alert to cloth wherever it appears, notes the domestic touch of a tiny bed curtained in white in the distance to the right. You can see it if you look hard and with patience, which is what Hills assumes a viewer must do.

Previously this viewer had ignored what, after Hills, is the oh-so-obvious presence of cloth. Turning to Titian, with whom the book concludes, there are for example the cloths (drapery, Hills tells us, cast down by the nymphs as told by Philostratus) piled before the playful putti in the center foreground of his Worship of Venus (1518-19). Or there is the great red swatch of cloth hanging beside Acteon advancing towards Diana defending herself against his eyes. I am not persuaded that the red curtain is there to dramatize Acteon’s fateful view of Diana. But why did Titian paint it there? And is it true that veils in Titian are a taking on and recognition of paint itself? It seems to me that the interpretive balance between paint and cloth which holds all thru this remarkable book is broken here without sufficient cause. Attractive though it may be as an critical account, I am not persuaded that Titian conceived of his veils as the equivalent of paint.

Reviewer Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.