By Kayleigh Whitman

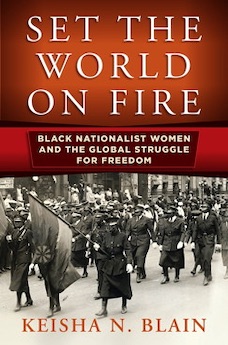

In 1978 William Jeremiah Moses published The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, 1850-1925. Though there were many parts of the book that raised readers’ eyebrows, the one thing that remained uncontested was the idea that the first generation of black nationalism ended with Marcus Garvey’s arrest and subsequent deportation. Between the internal collapse of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) just a few years after Garvey’s deportation and the rise of Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party during the 1960s, the movement was dormant, or at least that is what historians have been led to believe. Keisha Blain refutes this claim in her recent book Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. Based on extensive archival research, Blain argues that in between these two better-known periods, there was in fact a strong nationalist ferment spreading throughout the country. In the absence of male leadership, new opportunities were opened for black women of all classes to further the cause and redefine black nationalist politics on their own terms.

Blain defines black nationalism as the “political view that people of African descent constitute a separate group or nationality on the basis of their distinct culture, shared history, and experience.” This was often articulated through appeals to Pan-African unity, racial separatism, black pride, political self-determination, and economic self-sufficiency. Many, though not all, of the women chronicled in Blain’s text were part of the UNIA. However, this did not mean that they simply desired to extend the reach of the organization. Their “pragmatic” politics them a greater degree of flexibility and experimentation in the pursuit of their goals. Using print media, door to door campaigning, and public speeches, Amy Jacques Garvey, Celia Jane Allen, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, and others pursued a vision of liberation that was shaped by their own experiences as African-American women.

One of the more peculiar alliances that the women made was with white supremacists in the South during the height of Jim Crow. After FDR’s administration refused to set aside funds to purchase land in Liberia for black emigration, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon’s organization the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME) decided to direct its efforts below the Mason-Dixon. Celia Jane Allen was sent to Mississippi in order to garner support for emigration. While there she built essential networks with religious leaders, sharecroppers, and Senator Theodore G. Bilbo. Like Marcus Garvey and white supremacists, these women believed in racial essentialism and that the departure of black people from the United States would best serve their political and economic interests. Allen’s communications with Bilbo led to the introduction of the Greater Liberia or “Back to Africa” Bill in 1939. Though it was ultimately defeated, Blain suggests that there are two things to be learned: these black nationalist women would use whatever means were available to them to reach their goal and that they were impacting national politics in their pursuit.

This is not just limited to the domestic sphere either. Blain is very attentive to the international connections the women were attempting to make. For example, Gordon tried on multiple occasions to create connections with Japanese political leaders. Though these were never as successful as Gordon would have liked, they were effective enough for the F.B.I. to have her arrested on charges of sedition and conspiracy in 1942. When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Amy Ashwood, first wife of Marcus Garvey, joined other members of the International African Service Bureau in London’s Trafalgar Square to defend the country against imperial attack. Ashwood gave a powerful speech denouncing colonialism and reminding listeners of the history of African suffering at the hands of white countries.

Set the World on Fire’s alternative periodization raises many new considerations for scholars. If the 1930s through the 1950s experienced a prominent black nationalist presence (Blain often returns to the fact that the PME collected 400,000 signatures in support of black emigration), does it change our histories of race relations during the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War? Blain provides the clearest answers in regards to the first two, but this reviewer is suspicious that the text could open up some new avenues of inquiry in regards to the latter period. Additionally, what does Blain’s intervention tell us about how historians understand power? The women contained in the pages of Set the World on Fire were clearly active during the period in question, but why were their actions illegible to historians? Blain’s book reminds us of the ways that women have been able to shape national and international political dialogue, and yet have remained overshadowed by their male contemporaries.

Keisha Blain’s powerful book has filled both a chronological and scholarly gap in the history of black nationalism. The women that Blain describes, though perhaps not successful by the standards of other civil rights organizations, served as a critical bridge between the two more prominent periods. Later organizations like the Black Panther Party would develop platforms that in many ways mirrored the goals of Allen, Gordon, and their peers, who had been active in urban spaces such as Detroit where the BPP took root. These women’s commitments to political and economic sovereignty, racial pride, and Pan-African unity opened up spaces for later activists to continue their fight for equality.

Kayleigh Whitman (ΦBK, Florida State University, 2014) recently completed her Master’s degree in history at Brandeis University. Brandeis University is home to the Mu of Massachusetts chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.