Shortlisted for the 2017 Christian Gauss Award

By David Madden

What would you expect of a Jewish Bronx hoodlum who grew up to write fifty distinguished works of fiction and nonfiction? Bitter Bronx? Well, yes, but surely not I Am Abraham, one of the finest novels about Lincoln. But there you are. Certainly not The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson: A Novel. But you can buy it. Above all, you would not expect one of the most distinctively different critical works on Emily Dickinson.

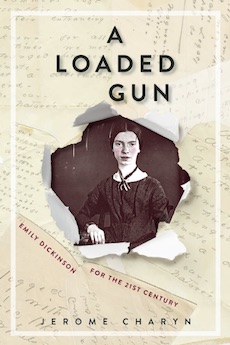

Jerome Charyn’s A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century is the scholarly equivalent of breaking and entering. Better still, full of quotations from her poetry, quotations from scholarly studies, and the author’s insights, it is like an interactive website.

He delineates ways in which Emily is many people. He delves into the issue of whether Emily was bisexual, her sister-in-law Sue being her greatest love. Providing supportive biographical anecdotes and lines of her poetry, he alludes to the many terms scholars apply to her: an innocent in white, a huntress and predator, a split personality, a prisoner, queen recluse, a performance artist, a kangaroo, a monster, a mermaid, a consumptive, an agoraphobic, a red-haired madwoman, a volcano, and her own description of her life: “My life had stood—a loaded gun.” Charyn’s subtitle suggests the modernity of a poet who “feels more contemporary than we are.” In life and art, she was an experimenter. Given her general witchery, “Cotton Mather would have burned her at the stake,” said poet-critic Allen Tate.

With unusual liveliness, Charyn describes the insights into the mysteries of the poet’s life and works of a plethora of Dickinson scholars, including Joyce Carol Oates, ending often with “I am not convinced,” then tells why not, and states his own, usually daring, audacious, fresh insights. His chapter on Emily’s “daemon dog” Carlo is his own distinctive contribution to the critical record. Even his profiles of scholars who are obsessed with Emily are fascinating, memorable.

All Emily’s relationships—with her father and her mother, her brother and her sister, her three women friends, her male admirers, including her publisher—were fraught with strange complications and conflicts that Charyn delineates.

This book provides unusual instances of Emily’s style, her sometimes violent, “whiplash language,” illuminating her use of dashes, her “zero at the bone imagery.” Her phrase “a woe of ecstasy” may best express her temperament.

Charyn’s line of thought zig-zags a little now and then. His style at times gets a little repetitive, contrived, and tiresome, but usually it is startling, inventive, and vibrant with expressive energy. “She was carrying bombs in her bosom.” Now and then, one may feel, probably without reproach, that what one experiences more than the many facets of Emily’s life and works is Charyn’s own myriad mind and imagination.

One way to take on this short book is to read it before, or during, or after a 4 o’clock martini or a swig or two of moonshine.

David Madden’s (ΦBK, University of Tennessee, 1979) latest book is Marble Goddesses and Mortal Flesh, four novellas. He has just finished My Creative Life in the Army, A Memoir and a memoir of his mother.