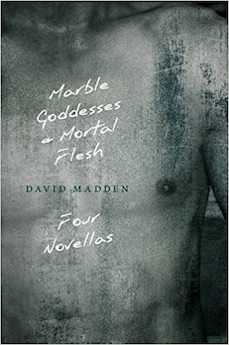

Archaeology of the Imagination: David Madden’s Marble Goddesses and Mortal Flesh, a collection of novellas, explores a writer’s journey.

By Sean Kinch

David Madden’s new collection of novellas, Marble Goddess and Mortal Flesh, is a trip down memory lane. The tales collected here, originally published in the 1960s and ‘70s, sketch scenes from the life of Lucius Hutchfield, the Knoxville native’s alter ego. They trace the arc of an artist’s journey and testify to the power of a writer who continues to find innovative ways to entertain and instruct readers.

In the title novella, Lucius Hutchfield, a successful writer now in his thirties, returns to the movie theater in Knoxville where he once worked as an usher. Revisiting the scene that excited his teenage imagination with images of “marble goddesses”—cinematic vixens Lana Turner, Vivien Leigh, Hedy Lamarr, and Veronica Lake—he takes the time to look through stacks of fiction he wrote as a child: “I’d let my will rest and encourage bizarre, surreal images to show up on the movie screen of my mind,” he recalls. “Descriptions of LSD trips pale in comparison beside my memory of those imagistic orgies.”

The spirit of Thomas Wolfe animates these stories—in the spewing passions of Madden’s characters, in their unbridled lusts and inchoate longings, in the turgid exuberance of Madden’s own prose. Lucius buys a copy of Wolfe’s Of Time and the River for the train ride to Knoxville and recalls writing, at age fourteen, an impassioned letter to Wolfe’s sister, asking for a summer job as caretaker for the Thomas Wolfe Home in Asheville: “Of the many admirers of Tom Wolfe I like to pride myself in the belief that I am the most ardent. I have a story to tell, which is as real, ugly, tragic, pitiful, sinful, and as much an obsession for me as the one Tom told so beautifully.”

In the other three novellas, Lucius encounters desperate characters whose lives hang in the balance. As a nineteen-year-old Merchant Marine in “The Hero and the Witness,” he attempts to stop the ship’s crew from persecuting his Argentinian bunkmate, a flamboyant man whose superior airs provoke savage violence. In “To Play the Con,” Lucius rushes to Georgia in a frenzied effort to keep his younger brother, convicted of passing bad checks, off the chain gang. Crime plays a less immediate role in “Nothing Dies, But Something Mourns,” where Lucius tracks down a ninety-five-year-old woman, reputed to have been Jesse James’s lover in her teens, before the hotel where she has lived for eighty years is torn down to clear a path for a new highway.

Beneath the primary level of conflict in these tales, Madden’s deeper concerns regarding the act of storytelling itself emerge. Lucius continually reflects on his role as author, on his ethical obligation to the people whose lives he exposes. Zara Jane Ransom cuts off her story before revealing the climax of her affair with Jesse James, leaving Lucius to finish the tale however he sees fit. “I’m not being mean-hearted,” Miss Ransom tells him, “for by stopping here, I surrender it all to your imagination.” Though Lucius renders a plausible conclusion, one that conforms to the known facts of the characters’ lives, “he felt a strange itch to know the truth.”

To phrase the problem differently, Lucius draws a distinction between truth and facts. He believes that “fiction, when its images were charged to the highest degree with meaning, was truth.” He also believes that “to make fiction agile … one must cripple fact.” And yet, despite his conviction that knowing the truth of whether Miss Ransom lost her “maidenhead” to Jesse James “would change nothing,” Lucius still wants to know what actually happened. Madden is grappling simultaneously with a number of perennial, irresolvable issues, but in the end they all reveal that, in the realm of human affairs, mystery is inescapable. As Lucius learns early on, “The thing about people is, you never know.”

Readers new to Madden’s fiction will find in Marble Goddesses and Mortal Flesh a fair introduction to the author’s recurring themes and stylistic panache. For longtime fans, this book, like Madden’s 2014 collection, The Last Bizarre Tale, will provide ample evidence that David Madden remains a remarkable archaeologist of the mind.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches in Nashville.

David Madden is a Phi Beta Kappa member inducted at the University of Tennessee in 1979.

This review was originally published November 14, 2017 by Chapter 16: A Community of Tennessee Writers, Readers & Passersby. Republished courtesy of Humanities Tennessee.