By Svetlana Alpers

David Thomson’s Warner Bros. is part of the Jewish Lives series published by Yale. It is a series that has worked: interesting, weighty, important people, Jewish people, are presented with verve in a snappy, economical format than you can read through quickly. Many of the authors are smart enough and good enough at writing so that you want to hold on to the book and read it again.

Thomson loves the movies and believes in them, which is to say he knows that they are false and deceitful and that that knowledge is part of his belief. Even as he is drawn in by the screen, he remains observant and wary. He loves stories. His wonderful book Moments That Made the Movies (2013) does not focus on the cinematic construction of a single frame (my taste), but on the role of a frame in the forward thrust of a story.

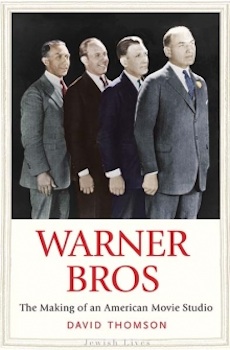

In this book, his story-telling is hooked up to the role Jews played in the making of Americans and America—the hero being Jack Warner, one of the four brothers Thomson describes right off as “maybe the biggest scum-bag to ever get into a Jewish Lives series.” Polish by parental birth, the newly named Warners had first arrived in Canada (where Jack was born in 1892) before the move to the United States. With American people, as with the American movies they make, Thomson has a feel for the uncertain, ambiguous, self-defeating aspects of the human scene. That is behind his fast thinking, talking, and writing or rather his talking through writing.

Warner Bros. turned to sound early with The Jazz Singer (1927) and threw itself into facing the depressed state of the county in the early 1930s. Thomson’s historical engagement with the making of America and Americans enters into the thick of all of that. A marvelous account of Paul Muni ‘s self-defining last words, “I steal,” in Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1931) has little to do with the brothers Warner, but more with the quickness of the new moviespeak and the fact that the mainstream of American movies “has never liked to admit that bad luck can kill us.” While he is thinking about chain gangs, Thomson remarks that Rikers Island is still in operation. In love with its movies, Thomson, British by birth and not Jewish, sustains uncertainty along with love for America.

During the terrible days of the ‘30s, Warner Bros. distracted the country with musical comedies and gangsters. Thomson begins this account with Gold Diggers of 1933 and the marvelous scene, situated as a finale, of Joan Blondell, a blond hooker singing “My Forgotten Man” while a Busby Berkeley pageant of soldiers triumphantly goes off to war and returns destroyed. Busby Berkeley’s pageant is here suggestively compared to the visual style of Leni Riefenstahl. Thomson’s detailed observations and discriminations are fine. They are what count.

The following chapter begins with the question, “Where does it begin, this American passion for outlaw identification, as if bursting to admit that the land of the free and the home of the brave may be a casino where nerve will finesse brio?” Coming up to date, that paragraph ends with the remark that we not only have Thomas Jefferson and Martin Luther King Jr. but W.C Fields and Donald Trump too. And so we are into gangster films which are attributed to Jack Warner though by now we are off and running with Bette Davis and then Joan Crawford and so into the wise and witty biographical account of film stars that makes Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary (2010) indispensable reading. Thomson is fine here on Bogart, about whom elsewhere he has written with certain reservations. Take his quick, passing remark about Bogart and Bacall in To Have or Have Not (1944) as being “Lolita without a breath of guilt.”

The last chapter takes us up to Jack Warner’s death in 1978. And in closing, Thomson sums up, once again in ringing words, his sense of movies past and the present from which he views them: “America has become a tedious doom-ridden country now. But in those precious years it hated to be boring. It would kiss you if it hadn’t just washed its hair.” (The last sentence is a take off from Bette Davis’ words in the 1932 Warner Bros. film The Cabin in the Cotton.)

But before that conclusion, he has left the Jewish life, or rather Jewish Lives, far behind. To get back to the series with which I began, this particular book is a good, quick read like the other books, but I am not sure I want to read it again. I do want to take a look at Gold Diggers of 1933 and other old Warner Bros. films that Thomson brings to new life here.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic, and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.