By Lewis Fried

Jane Jacobs caught public attention with her now-classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961. Her study of the intricacies of the living natures and structures (and I use those words with some caution) of the city, of the plethora of people, places, and transactions that give the city its characteristic valences and densities—marked her as an “original.” She had not only brought before the reader’s eye dramatic examples of the city as a multifaceted, organized and organizing phenomena, but also illuminated the gifts and problems the city presented. As Laurence puts it, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jacobs hoped to create “a foundation of knowledge about how the city works.”

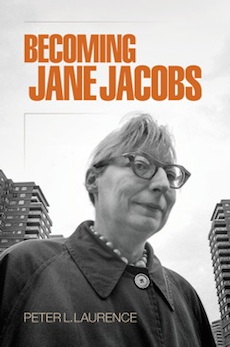

Was she really an obscure, untutored figure before her book was published—as popular belief has it? Jane Jacobs was not unknown; her understanding of the city had been cultivated for decades. The grand virtue of Laurence’s absorbing study of Jacobs is found in the key-word of the title: “Becoming.” This book is a major intellectual contribution, a meticulous study of the development of her thought, most specifically of the ideas found in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, as well as the key concepts found in her later writing. Laurence clears the fog that shrouded Jacobs’ development from the general public. Doing so, he also reveals the excitement of then-contemporary urban thought and design.

Her comprehension of what the city was, and how it remained habitable, was strengthened by walking it. Coming from Scranton as a young woman, Jacobs found in New York, especially the Village, another home, a place for employment, an opportunity for further education, and a laboratory. She served her journeyman years on The Iron Age, a magazine devoted to the metals industry. In that endeavor, as Laurence notes, she studied an “elemental part” of regional and national economy. In addition, she worked as a freelance writer for the Herald Tribune and then, in 1943, became a writer for the Office of War Information, editing and writing propaganda. An important phase of her work finds her at Amerika, for six years as a writer and editor, conveying to a Russian readership approved renditions of national life.

This period ended unhappily. She had applied for a visa to visit Siberia and had asked Alger Hiss, a supervisor, for help. She was tagged by the FBI, caught up in the web of McCarthyism, and was investigated by the Loyalty Security Board; Amerika was relocated to Washington, D.C. She remained in New York. However, there was a felicitous consequence: she became part of the editorial circle at Architectural Forum when its editor, Douglas Haskell, pushed it to develop an aggressive critique of American city planning and architecture. She, Haskell, and the Forum played an indispensable part in a reconsideration of what urban planning had been, what it was, and what it might well be.

The initial plan of her book addressed five major topics: “street, park, scale, mixture, and focal centers.” As the book matured, these topics became more detailed and comprehensive, with a concern for fundamental patterns of orders in process that ensured stability and flexibility. Laurence’s impressive study also traces how Jacobs’ “on the ground” political work to save, for example, a neighborhood or a park, also changed her mind about what design and meaningful planning were. The city had to accommodate people’s needs—not the other way around.

Her ideas of city planning were consequential. What was not to be taken at face value was massive clearance, massive housing projects, and conventional highway worship. Lives could not be graphed; human relations were often most thick and valuable when they were found in those socially functional places urban designers wanted to demolish. For example, ridding a street of small stores also eradicated places for meetings, for advice, for worship, for community well-being. What had to be maintained was often dismissed by top-down planners; what was often ignored were those foci neighborhood people took as their own—and necessarily so. (I am reminded of the central clearing house of information in my own Queens neighborhood in the early 60s—Bernie’s candy store. ) All these made for eyes on the street as well as fascinating streets for eyes. People going about their lives performed an urban “ballet.”

Her major book gave the public a new sense of what functional urban phenomena were as well as the complexity of urban decay. What The Death and Life of Great American Cities bequeathed—and still does—is how our lives are given expression and possibility by the humanly-made environment, no matter how small the details, far more than we had hitherto imagined.

Lewis Fried (ΦBK, Queen’s College, CUNY, 1964) is Professor of English Emeritus at Kent State University and a resident member of the Nu of Ohio Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.