By Svetlana Alpers

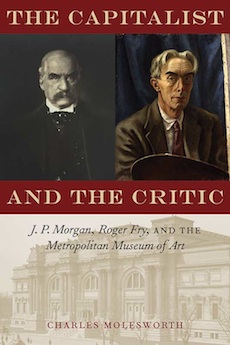

This is in some ways a lackluster book: the information seems often to have been acquired at second hand from other publications (Morgan has been a favorite topic for authors) and the writing can be stiff. However, the topic is a relevant one today, and it got me thinking: J.P. Morgan (1837-1913) for thinking about museums, collecting, and collections; and Roger Fry (1866-1934) for the deep pleasures in looking at art and its relationship to commerce.

You have to press your way through rather hard going about Morgan on his own at the beginning of the book to get to the heart of the matter—Fry among the connoisseurs of Europe and England and his discovery in New York of the New World of collectors and museums, and after. Fry is closer to the author’s heart than Morgan, but what interests him is the relationship between art and commerce, which explains the presence of the two of them in the book.

Why, one might wonder, is there such an uproar in the art world today about the power of money when it was already present in the United States over a hundred years ago when Morgan was the power at the Met (in place on the Met board of trustees and finally president from 1888-1913), at the American Museum of Natural History, the Hartford Wadsworth Atheneum, as well as being a founder of the American Academy in Rome? Unlike European countries whose citizens have effectively, for better or worse, paid the government to deal with such cultural things, in America there has long been a dependence on the authority of private wealth.

Fry, when first called to New York in 1905-06, was a painter, art writer, connoisseur (in touch with and also in conflict with Berenson). He had recently helped found The Burlington Magazine—its original forward looking views have become traditional by now, but it is still a fine monthly art journal that publishes some of the smartest exhibition reviews anywhere. The inaugural issue had an editorial (presumably by Fry) warning of commerce and collecting as the enemies of the appreciation of art. Molesworth points out that in New York, in the Met’s Bulletin, Fry’s Idea of a Gallery that assumed European painting to be the great historical tradition to be collected with imaginative and faithful (faith was an important word for him) attention to be encouraged, was flanked by an article on some American landscape paintings and one on busts of Benjamin Franklin done after life.

It gives one pause to read Fry’s collecting and educational notions for a museum when we have recently read in the New York Times that this past year the Met (though its debt is rising) recorded the largest number of visitors ever (an amazing 6.7 million) and that the most visited shows were Cornelia Parker’s tribute to Hitchcock’s Psycho on the roof and a show at the Costume Institute. We have come far from the art Fry and Morgan championed just over 100 years ago, but clearly other things were also in play back then.

Fry worked first as a curator, then was demoted to an agent for the Metropolitan Museum. There is an interesting account here of a buying trip through Italy that Fry took with Morgan in 1907. But things were not working out—the Met questioned the conservation of paintings authorized by Fry, and Fry was agitated by the conflict between Morgan buying art for himself (at issue was a Fra Angelico Madonna) and art for the museum. When Fry, in his normal frank and unpolitic way, brought the matter up, his employment came to an end. (The painting, no longer attributed to Fra Angelico, is now in the Thyssen Collection in Madrid.)

The book goes on to follow Morgan’s last years: establishing various permanent departments at the Met and turning to the collecting of Egyptian art. Fry, back in England, turns his back on historic art and becomes a prophet of the new—the central figure for him being Paul Cezanne and what he dubbed post-impressionism, which was focused in his much-attacked 1910 Manet and the Post –Impressionists exhibit.

The book concludes with a consideration of Fry’s continued attention to the question of art and commerce: his failure in founding the craft–oriented Omega Workshop and his grappling with the problem of the monetary value of art, its aesthetic value, and the individuals and public involved with each. Fry believed, fervently believed in fact, that to his despair society had an interest in “inoculating” people against art. The solution to that at the present time seems to be to make exhibits and promote art that goes down easily with the public—whether on the roof of the Met or in the galleries of its Costume Institute. Morgan and Fry would have been at one in resisting that.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Art History at New York University.