By Colin Rafferty

A remarkable thing happens close to halfway through Rachel Sussman’s The Oldest Living Things in the World, ostensibly a book of photographs of continuously living organisms at least two millennia old: Rachel Sussman shows up. Of course, she’s been in the book all along, taking photographs of ancient organisms on all seven continents, narrating the sometimes difficult journeys she takes to reach them; however, this has been in her role as a photographer whose work has appeared in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. When she reaches Europe to shoot a 3,000 year old olive tree in Greece, the text that accompanies the photographs tells not only the story of the journey to the tree, but the end of a journey of Sussman’s. She realizes that she and her companion, referred to only as “R” throughout the book, “should no longer be together,” and they will part after their return from this trip.

This simple moment—one half of a couple realizing the end of the relationship—forms the basis for many great works of literature, but it’s surprising to encounter it in what certainly appears to be a coffee table book. Ultimately, though, this humanity provides The Oldest Living Things in the World with a vitality that couldn’t have existed in a book of only photographs. The juxtaposition of Sussman’s own fragile humanity—and by extension, all of ours—with the seeming permanence of these organisms gives the book a powerful energy that emphasizes the passage of time both slow and fast.

Do not mistake this book for a tell-all memoir, however. Sussman’s own life is a foil to the narratives of these hardy living things. The vast majority of the book is dedicated to explaining the histories and futures of these organisms, which vary in age from 2,000 (brain coral in Tobago) to a half-million years (Siberian actinobacteria). Sussman records how they have survived for all these years thanks to (and occasionally in spite of) nature and humanity, and the steps that naturalists and other humans are taking to protect them. Sometimes all Sussman can do is record the remains of recently deceased individuals—for example, the Senator, a 3,500 year old cypress tree in Florida, fell victim to arsonists during the duration of Sussman’s project (having put off traveling to the tree several times in favor of more remote locations, Sussman writes “surely, if it had been around for 3,500 years, it was going to be around for 3,505”).

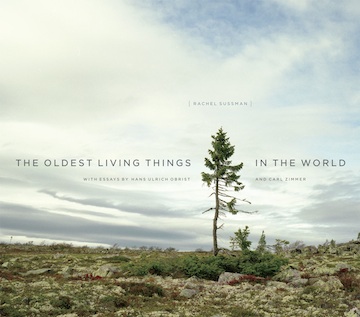

Although this book exists as a electronic book, it is difficult to imagine it in a more powerful form than the physical version. A large book, with beautiful full-color photographs throughout, this is a book to be experienced more than simply read. It is a cliché to say that a book can bring something to life, and yet Sussman’s words and photographs imbue her subjects with vitality.

Always, the specter of global climate change hangs over these organisms, threatening their continued existence (and, Sussman implies, our own). Very often, these organisms, which sometimes have been witnesses to all of recorded history, face destruction unless humans—simultaneously their protectors and destroyers—take action. And this idea forms the core of The Oldest Living Things in the World; as Sussman writes, “one thing we do share: as long as a wound isn’t too deep, we can—and do—heal.”

Colin Rafferty (ΦBK, Kansas State University, 1998) teaches nonfiction writing at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Mary Washington is home to the Kappa of Virginia Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.