By Svetlana Alpers

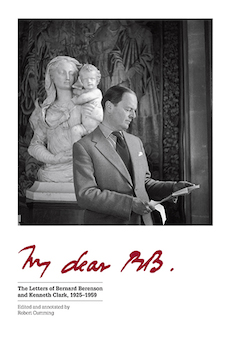

This book of letters takes one back to another time: to Berenson (1865-1959) a great, long-lived Jewish-born art critic, connoisseur, and consultant to art dealers, who loved gracefully through the second World War in Mussolini’s Italy and to the well-born and well-bred Kenneth Clark (1903-1983), appointed Director of the National Gallery of London at the age of 31.

The two meet at I Tatti in 1925 (Berenson was 60, Clark 23) with Clark, still an undergraduate at Oxford, immediately being invited back to help prepare the publication of Berenson’s Drawings of the Florentine Painters. He eventually took up the post (after discussion about when it would be best for him to arrive with his car and chauffeur). The cataloging did not work out and Clark was eventually fired—but the friendship had started. After the firing, the friendship was much improved, sometimes to be elaborately defined in the letters of each.

Against Berenson’s advice, Clark accepted the offer to become director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and shortly after, this time with Berenson’s approval, he accepted the directorship of the National Gallery. We find out in the letters that Clark’s monies did a lot—adding an extension to the museum in Oxford, and entertaining royally, and royalty, when living in a grand house in Portland Place.

The correspondence is amply supported and clarified by the editor’s introductions to dated sections, epistolary annotations, and a Dramatis Personae or guide to people mentioned. Robert Cumming had close ties to the Berenson world. And indeed without his commentary the entire correspondence would be hard to make sense of.

It is in the introduction to the years 1933-39 that we learn, for example, that Clark’s imperious directorial ways infuriated the staff of the National Gallery and also of the extraordinarily intense travels conducted by both Clark and Berenson in the years just before the outbreak of war. Off the cuff remarks are at the heart of the letters: we read that for Clark, Titian’s Saint Margaret in the Prado is “almost the most beautiful picture in the world” and having bought a Rembrandt Saskia for the National Gallery, “a rich romantic affair” he says he loves so much more than his “usual boring old men”; Berenson admits he prefers the prospect of trips to the Near East more than returning to England and he chastises Clark for his (famously mistaken) purchase of four so-called “Giorgiones.” Clark speaks enthusiastically about his book of details of paintings in the Gallery, the notes for which “will at least show the number of different ways in which a civilized person may look at picture.” As I said, that was another time.

After the hiatus of the war when then were out of contact, life and letters began again. I am struck in reading my notes how much more seems of interest in the Clark letters than in the Berenson ones. For example, Clark’s marvelous description on his first visit to Australia of a land that looked just like a painting by Piero della Francesca (he had in mind the Baptism in London), “The grass is white, the trunks of trees pinkish white, the leaves glaucous.” Or his persistent disappointment in the United States, ”I can’t face the mixture of heartiness and competition.” After lecturing on Uccello in Philadelphia he writes, ”On the whole people do not like a critical approach—they want information or uplift.”

As he ages, Berenson turns from art to life, “I feel less and less glad of seeing works of art, I see so many more of my own making every step I take out of doors, every time faces come my way. Yet when I do come across real (ie representational paintings or carvings) I enjoy them more than ever.” He turned more and more to his walks and his salon, with an endless stream of the famous at his table ( Walter Lippmann, Learned Hand, Harry Truman). But for the last years one should look at the publication of excerpts from his late diaries Sunset and Twilight—which indeed I was led to by this engaging book.

But lest we get nostalgic, let me give Clark the last word on Berenson as he published it in a ( surprisingly) amended version of his memorial encomium to read, “For almost fifty years Bernard Berenson knew himself to be a legendary figure. His delicate frame, his beautiful eyes, his slightly artificial courtesy and the tone of infallibility which he sustained in the unbroken line of conversation, made it very difficult to believe that this exquisite little conjurer was not bamboozling us but had made solid contributions to our knowledge and understanding of art.”

Along with their wealth and polished manners they were a sharp and outspoken pair.

Svetlana Alpers, an artist, critic and renowned art historian, is professor emerita of the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley and a visiting scholar in the Department of Fine Arts at New York University.