By David Madden

“I wish I were a better letter writer” is an irony that Warren often repeated, finally in a letter to Mary Barber, his sister, the last of almost 3,000 letters in six volumes, encompassing over six decades, the years from 1924 through 1989, raising the question among their readers: how good, readable, and relevant a letter writer was Robert Penn Warren?

Whatever the individual and collective answers, questions of selection for breakout volumes also will arise. For instance, given that some will regard the six volumes as too much, the most obvious consideration would be given to the question of a one-volume selected letters; Professor Randy Hendricks tells me he has pondered such a project. Another might be a volume comprising the most telling letters to a single recipient, such as Cleanth Brooks or Allen Tate, with a greater emphasis upon the literary life. A 400-page volume exists of such correspondence between Warren and Brooks, colleagues and friends throughout much of their adult lives. And such a volume of correspondence exists between Allen Tate and Donald Davidson, the Vanderbilt professor whose influence upon Tate, Warren, and many others was long-lastingly profound. Whether this monolithic collection of a writer’s correspondence is among the last to be generated from years preceding today’s entrenched electronic, cloud-hovering age is another question, poignantly relevant.

A Herculean task overall, a Sisyphean task volume by volume from 2002 to 2014, performed by William Bedford Clark, author of The American Vision of Robert Penn Warren; Randy Hendricks, author of Lonelier Than God: Robert Penn Warren And The Southern Exile; and James A. Perkins, author of The Cass Mastern Material: The Core Of Robert Penn Warren’s “All The King’s Men.” The six volumes of Warren correspondence are a major achievement for LSU Press’s Southern Literary Studies Series, founded in 1963 by the late Louis D. Rubin, Jr., carried on by eminent UNC scholar Fred Hobson, from 1993 to 2011.

As editor of the first two volumes and author of introductions for all six, Clark set the standard for selection and the methodology in the first volume, repeated with variations and additions in subsequent introductions, and in an elegant literary style, he has provided biographical information and astute guiding observations and insights for all six volumes. Clark urges readers to experience the letters not only as expressions of Warren as a person, but as a discrete canon that enhances the effects of his 40 volumes of work in all genres.

Hendricks tells me that the selection of letters probably entailed over 90 percent of archival material made available to the editors, with justification for embracing Warren’s inclination to repeat himself from letter to letter. Readers will do well to be mindful that a great many letters remain out there in the hands of persons and libraries, known, not yet known, or unavailable or inaccessible for a variety of reasons.

I miss seeing again in these volumes his often admitted wretched typing, such as I received in numerous postcards and the manuscript on Andrew Lytle’s The Long Night that he submitted at my request to a volume I conceived and edited entitled, Rediscoveries.

And those who knew him and heard him speak will hear, as they read these letters, his distinctive voice, high pitched and nasal that his wife Eleanor Clark, a very elegant lady and fine novelist, urged him to modify, especially when he gave public readings of his poetry or offered to read Dante aloud to her.

Bradford and Hendricks and Perkins are well aware, as seen in the letters, of course, that Warren was very kind and helpful to young writers, not only former students such as Mark Strand, Dave Smith, David Milch, and James Wilcox, but those he may have met once only, myself included. Along with his friend Saul Bellow, he chose my work for a Rockefeller Grant that enabled me to write my third novel in Venice a year after moving from Ohio University, where I had met him, to Louisiana State University, where I created the undergraduate program in writing because I wanted to live where he had taught, edited The Southern Review, and taken in the raw material for All the King’s Men.

Most of those who testified that he was not a particularly effective teacher are eager to stress his influence as a poet, critic, and novelist, and that he was an altogether very fine person. With Brooks, through their profoundly innovative textbooks, especially Understanding Fiction and Understanding Poetry, Warren may be regarded internationally as one of the greatest of teachers.

The editors came up with very pertinent titles for the volumes that evoke the life and the works of each period:

The Apprentice Years, 1924-1934. Warren left Guthrie, Kentucky at fifteen; letters do not reveal that his parents and siblings had much influence upon him; he went to high school in Clarksville, then to Vanderbilt, the University of California, and Oxford as Rhodes Scholar, taught here and there, and attempted suicide.

The Southern Review Years, 1935-1942. The focus is on the all-important Baton Rouge years. He makes many friendships and publishes in biography, criticism, textbooks, fiction, and poetry genres.

Triumph and Transition, 1943-1952 : Break-up of long, painful marriage, beginning of marriage to novelist Eleanor Clark, years in Rome, and teaching at Yale with Cleanth Brooks are featured people, places, and events.

New Beginnings and New Directions, 1953-1968: His children are born. He works on Audubon, Brother to Dragons, books on civil rights. He teaches at Yale School of Drama.

Backward Glances and New Visions, 1969-1979: He travels, writes his last two novels, publishes works on Melville, Whittier, and Dreiser, and concentrates more on writing poems than any other genre.

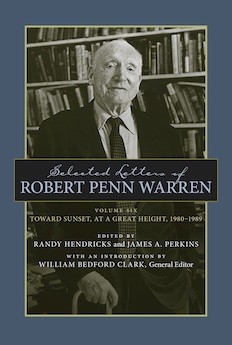

Finally, the sixth volume, Toward Sunset, At a Great Height, 1980-1989 contains letters to or comments about most of the still-living friends who figured in the early volumes.

Warren’s major correspondents throughout the six volumes are his teachers, John Crowe Ransom and Donald Davidson; his editors, Lambert Davis and Albert Erskine; his colleagues, Cleanth Brooks and Allen Tate; his closest friends, Andrew Lytle, Katherine Anne Porter, Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, and Eudora Welty; his students, Robert Lowell, Peter Taylor, Mark Strand; his critics, William Bedford Clark and Lewis Simpson; and his children, Rosanna and Gabriel. That a good many of them constitute a cohesive group, some from the Agrarian and Fugitive eras, is well-known. During the years of the final volume, most are dead or dying. Floyd Watkins, more than anyone else in those last years, elicits from Warren important comments on his life and works.

With the six volumes in hand, I realize that starting in 1952 when I attended a literary festival at the Women’s College of North Carolina as a University of Tennessee freshman, where I met Peter Taylor and Katherine Anne Porter, I have met almost all of those and other major players and known a good many well.

In 1960, approaching the entrance to Yale’s Bienecke Library, my arms overfull of books about Ezra Pound, I was glad to see a tall man in his mid-fifties opening the door for me, thanking him, but recognizing too late that the rough-hewn face was Robert Penn Warren’s.

Each volume contains welcome photographs of Warren’s family and friends. A separate literary thematic index would have added great value to these volumes, especially to the final volume, indexing all six retroactively on such subjects as the New Criticism and Warren’s concept of pure poetry. This final volume costs $90; $394.85, before tax, will enable Warren admirers to look upon all six on a shelf next to the fifty volumes of his complete works.

Winner early and late of many major prizes and awards and a deluge of praise from all quarters for his works as poet, novelist, critic, innovative teacher and textbook editor, and social commentator on the Civil War and civil rights, Warren was always self-effacing, but in a way that strikes me as a folksy adherence to Southern mores. Sadly, despite the efforts of members of the Robert Penn Warren Circle to stress his poetry as his greatest achievement, the reputation of our first Poet Laureate seems to be fading, but, one must hope, a reputation that generation after generation will revive.

David Madden is editor of The Legacy of Robert Penn Warren (2000). He has written in all genres, including many works of literary criticism. The latest of his thirteen works of fiction is The Last Bizarre Tale, stories. My Intellectual Life in the Army is a memoir in progress.